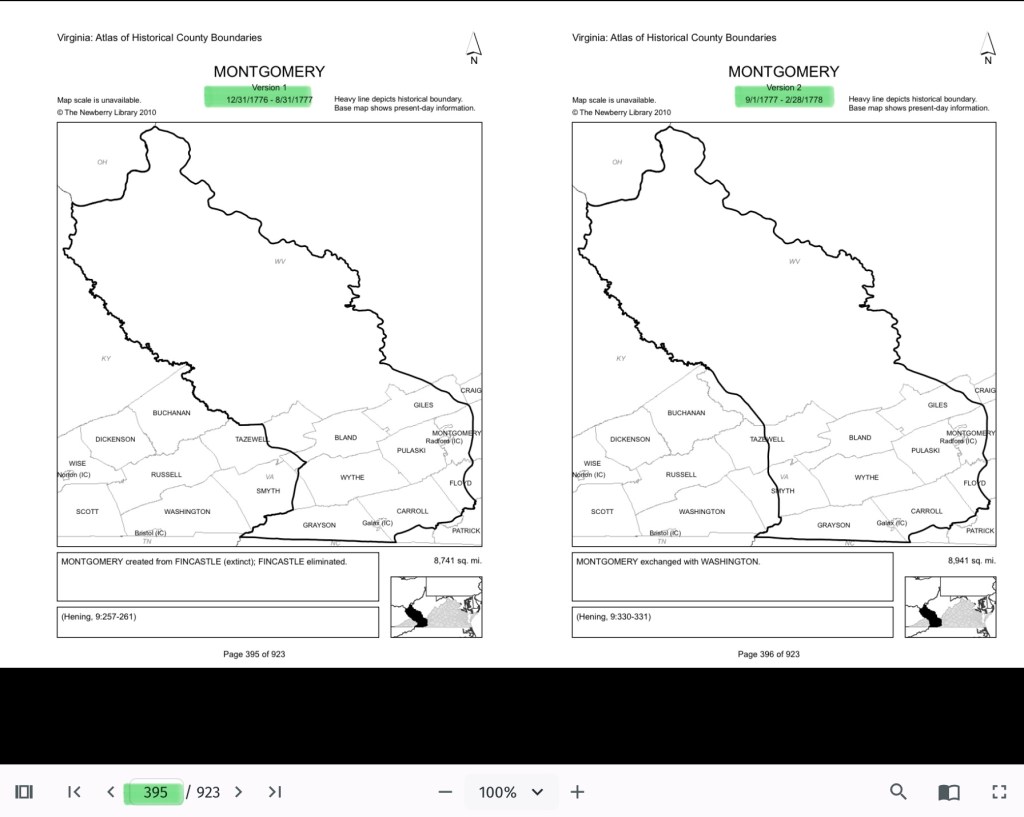

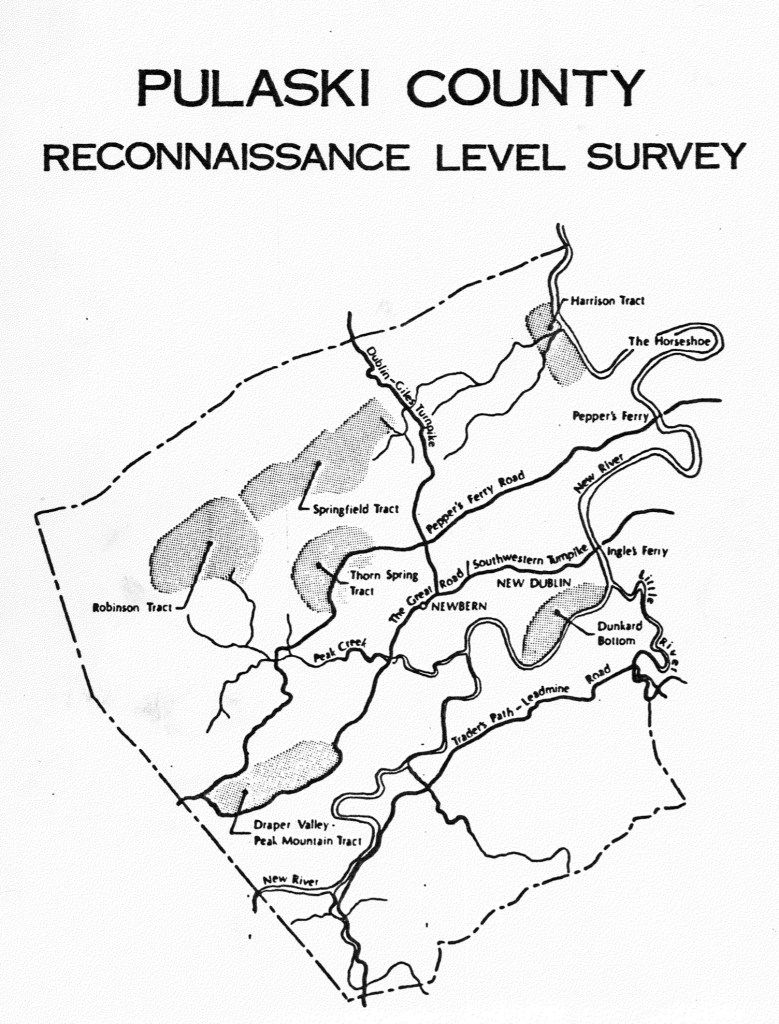

Montgomery County, Virginia, was slow to dismantle enforced racial separation in its schools, not doing so until September 1961. Neighboring counties followed a similar pace—Floyd in January 1961 and Pulaski in September 1961. (Martin, Black Education in Montgomery County 1939–1966, Virginia Tech master’s thesis, 1996).

After the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling outlawed segregation, Montgomery County resisted. The school board leaned on “states’ rights” arguments and used tactics from Virginia’s Gray Commission—such as controlling student assignments and offering tuition grants to white families—to delay integration for years.

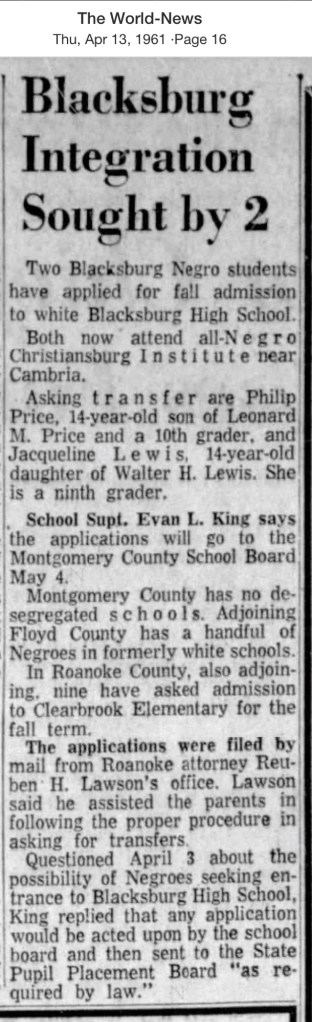

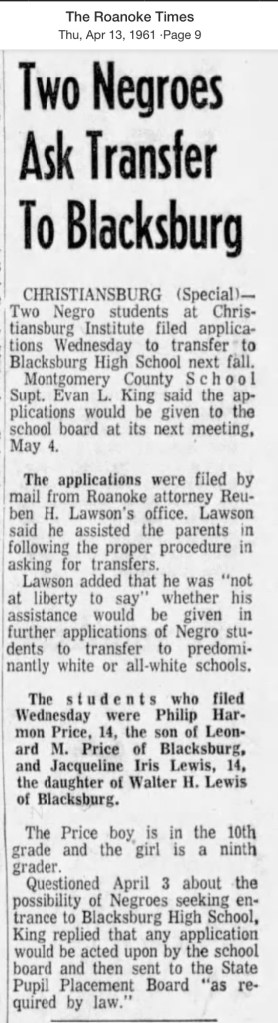

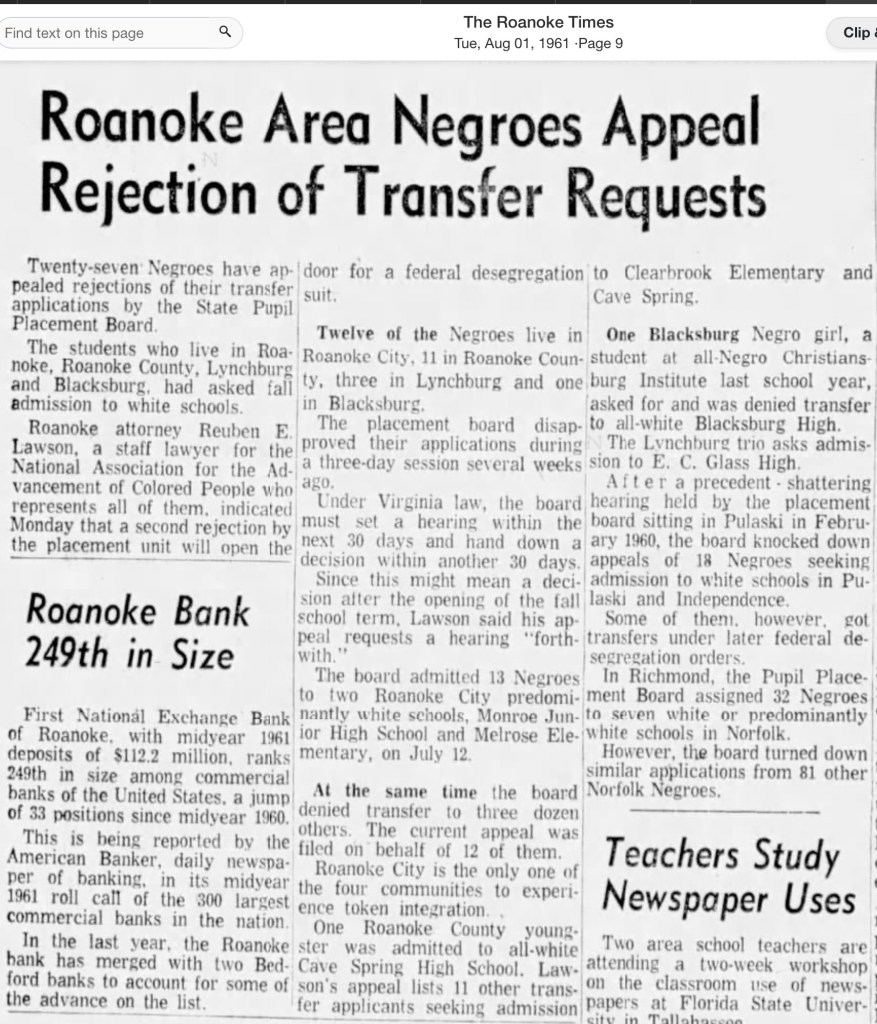

Amidst this resistance, three students from Christiansburg Institute applied to transfer to the all-white Blacksburg High School, which then enrolled about 900 students. They were siblings Phillip H. Price (15) and Ann Christine Price (13), along with Jacqueline Iris Lewis (14). With support from NAACP attorney Reuben E. Lawson of Roanoke, their applications went before the State Pupil Placement Board. Phillip and Ann Christine were admitted for the 1961 school year, but Jacqueline’s request was denied on the grounds of “academic standards”—a requirement never applied to white students.

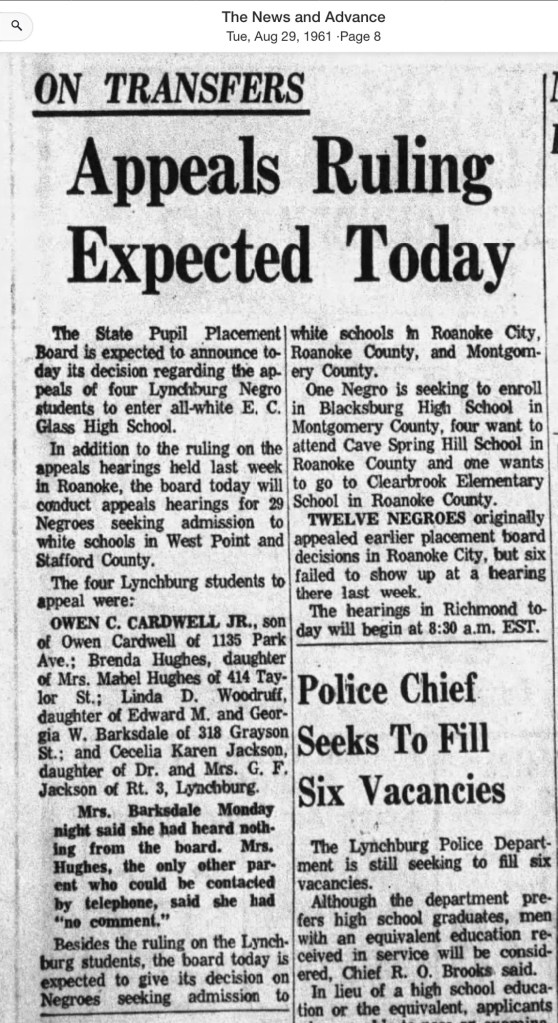

On August 23, 1961, Jacqueline and her father, Walter H. Lewis, traveled to Roanoke for the hearing, an intimidating experience for a 14-year-old. The Board delayed its ruling for a week before denying her appeal. That fall, Jacqueline remained at Christiansburg Institute.

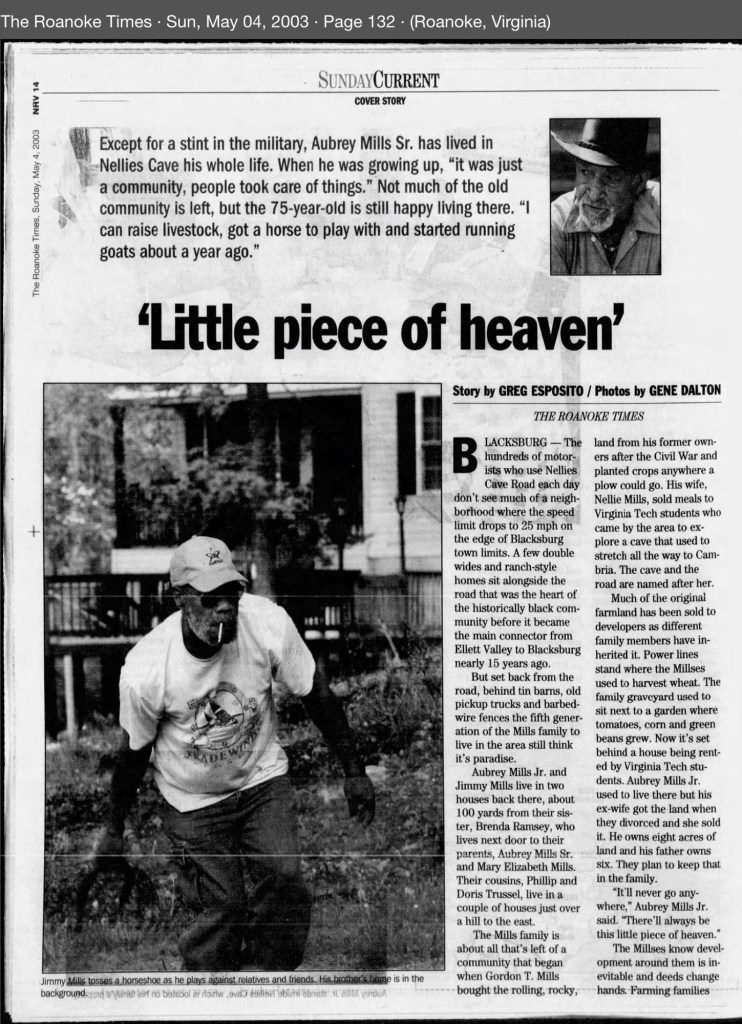

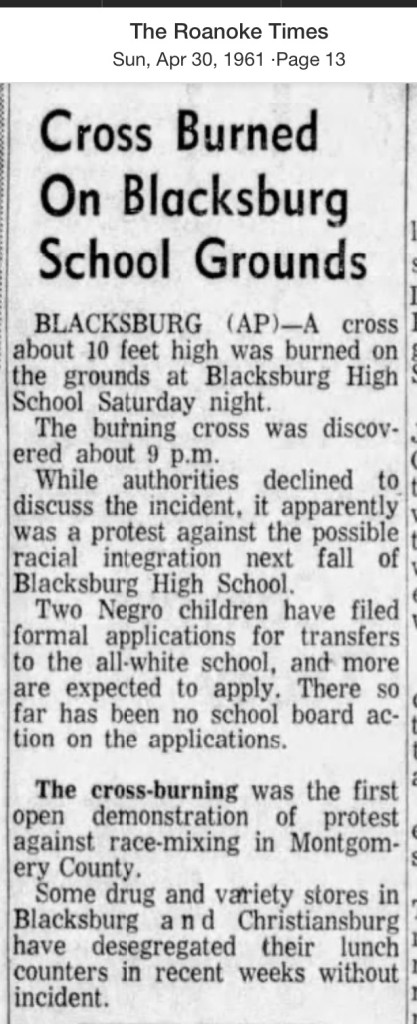

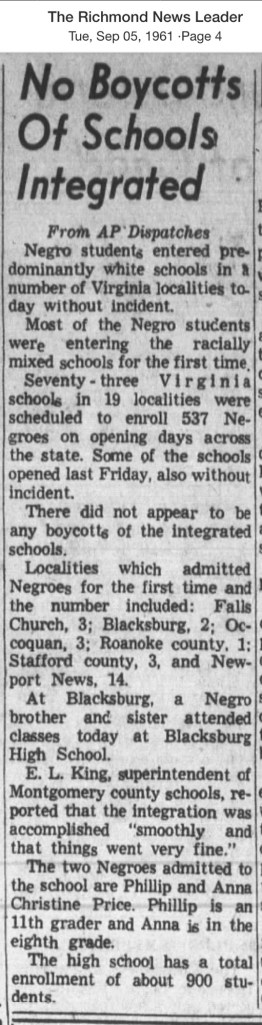

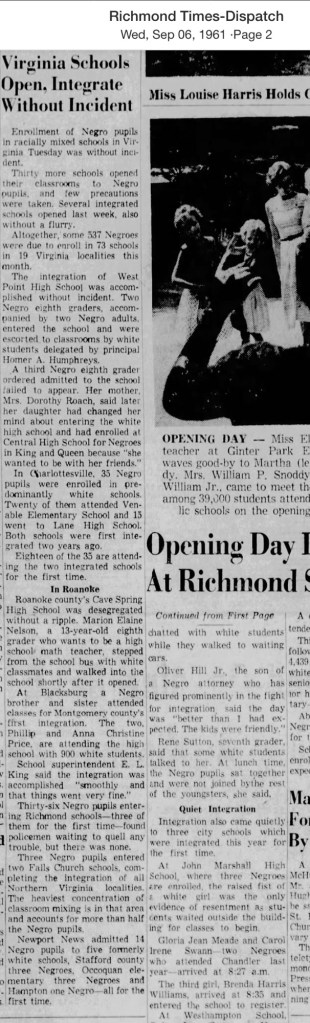

That September, Phillip and Ann Christine Price became the first Black students to integrate Montgomery County schools when they walked into Blacksburg High. According to researcher Tracy A. Martin, they were not alone—their white neighbors walked beside them in solidarity. This act of courage followed a chilling warning: on April 29, 1961, a ten-foot burning cross had been discovered on the school grounds, South Main Street.

In 1962, the school board again delayed the application process for two more students seeking admission. Yearbooks from 1961–1964 suggest that the Price siblings were the only African American students at Blacksburg High during those early years. In the years that followed, more students of color began to appear in the yearbooks. By 1966, the school board closed Christiansburg Institute, and all of the county’s white high schools were finally opened to every student.

Newspaper Articles

April 1961

July 1961

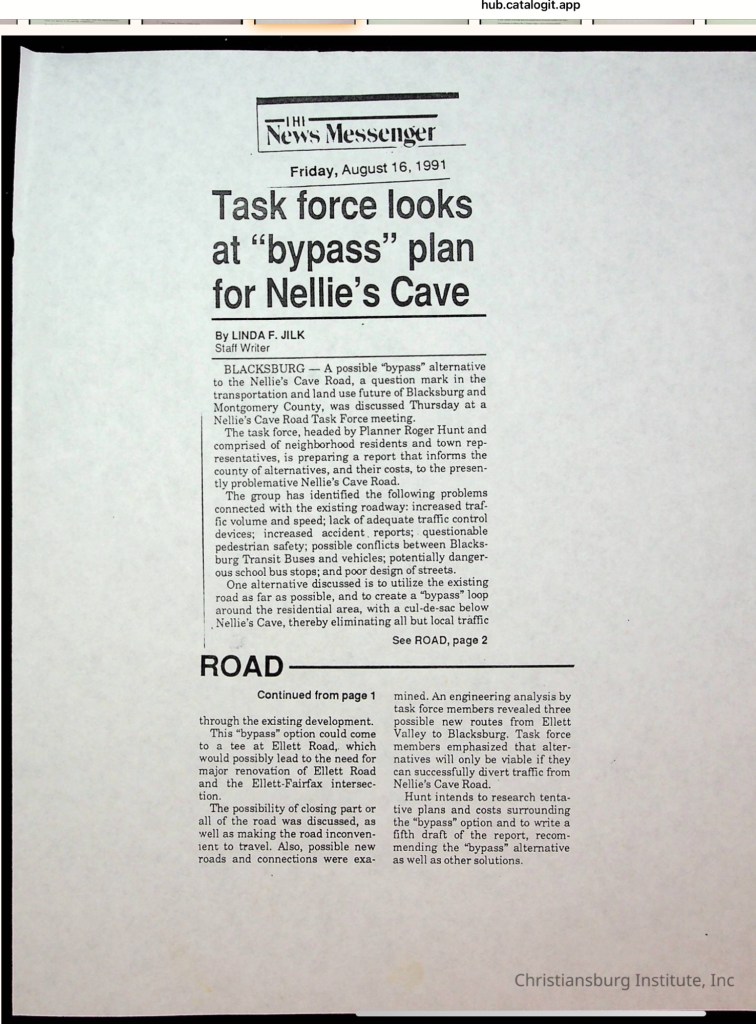

August 1961

September 1961

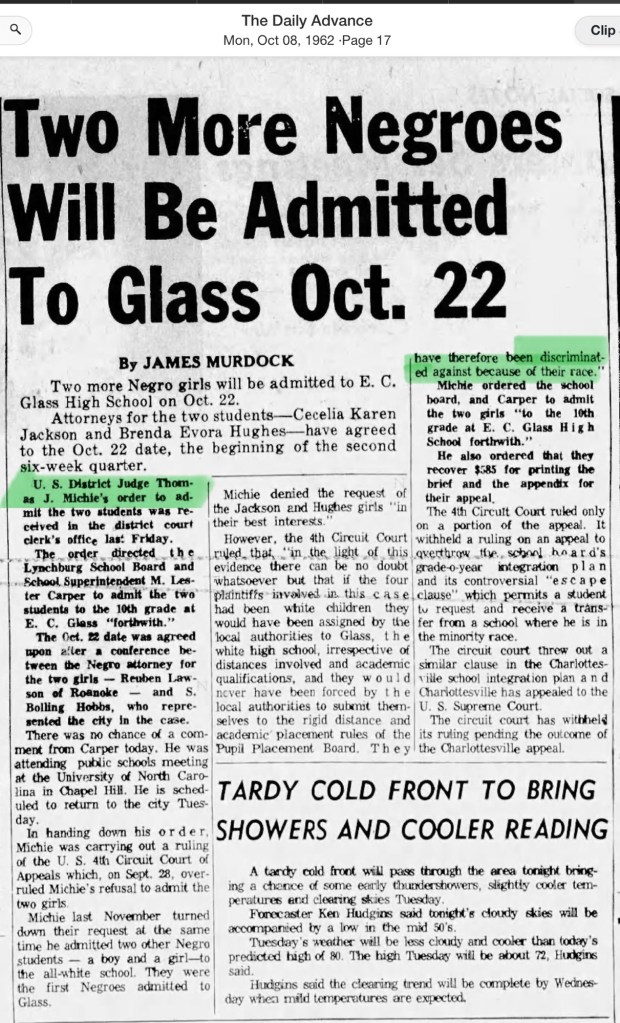

1962 Application of Two Young Women, the Courts Ruling