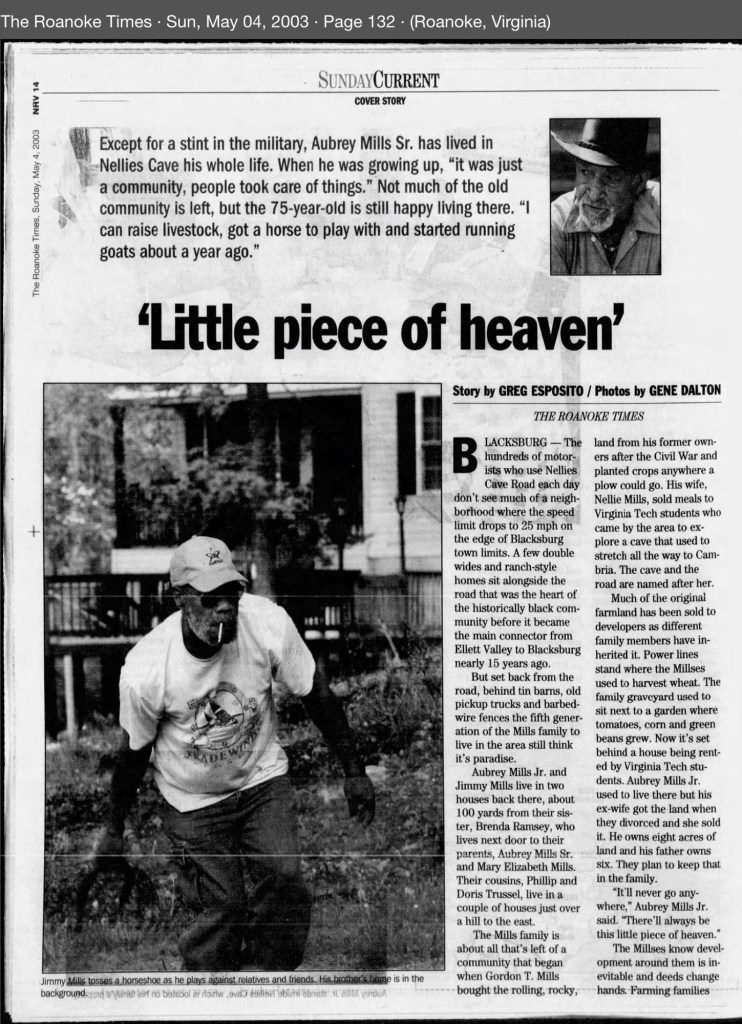

Alvin Duval Lester (b. 1947) is another example of the deep connections between Montgomery County families and Jackson Ward in Richmond. Raised in Christiansburg, Virginia, Alvin later documented life in Richmond through his photography. His images of Jackson Ward in the 1980s–90s were featured in the exhibit Alvin Lester: Portraits of Jackson Ward and Beyond. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts exhibit will run until March 30, 2026 in the Photography Gallery, Richmond, Virginia. Facebook post by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

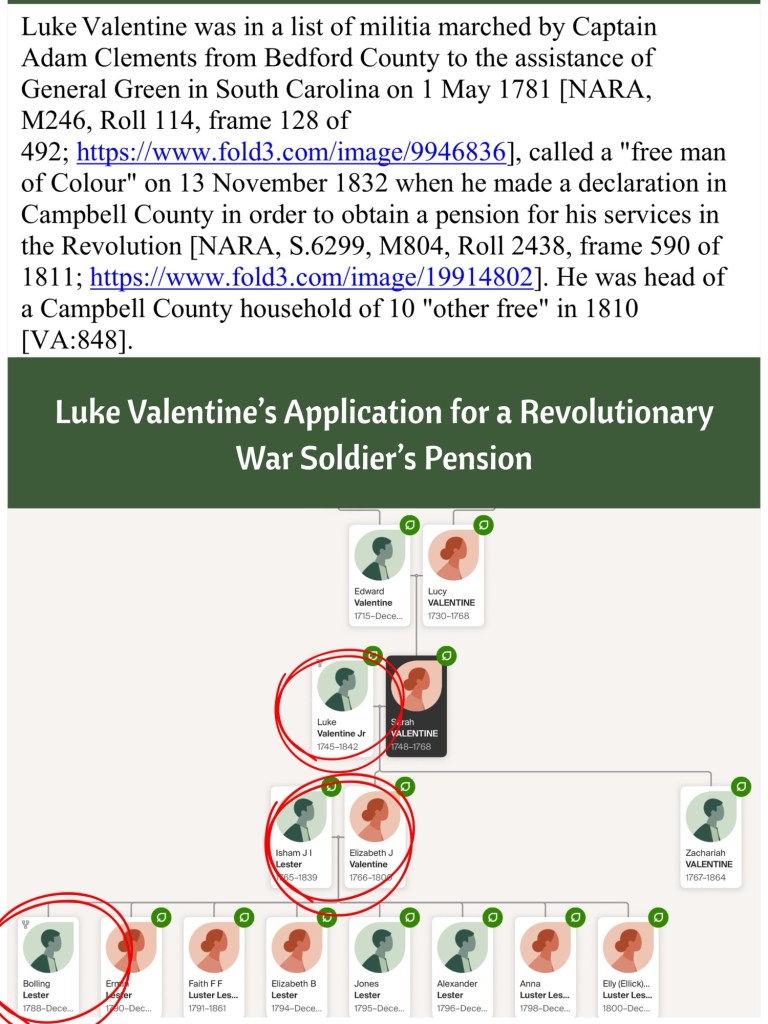

Alvin’s family history can be traced through at least five generations of free Black ancestors. His fourth-great-grandfather, Isham Lester (1765–1839), was listed as free in the 1810 U.S. Census for Lunenburg County. His son Bolling Lester, and grandson John C. Lester, were also born free there. By the 1860 U.S. Census, Bolling Lester had moved his family to Dry Valley in Montgomery County.

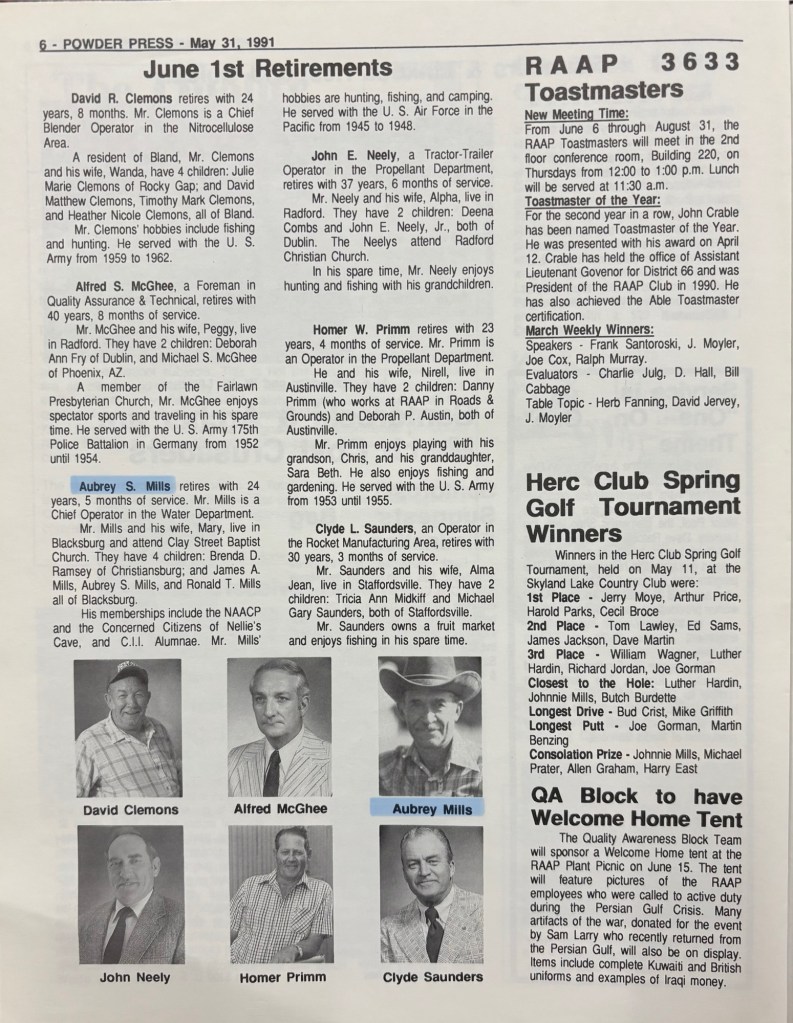

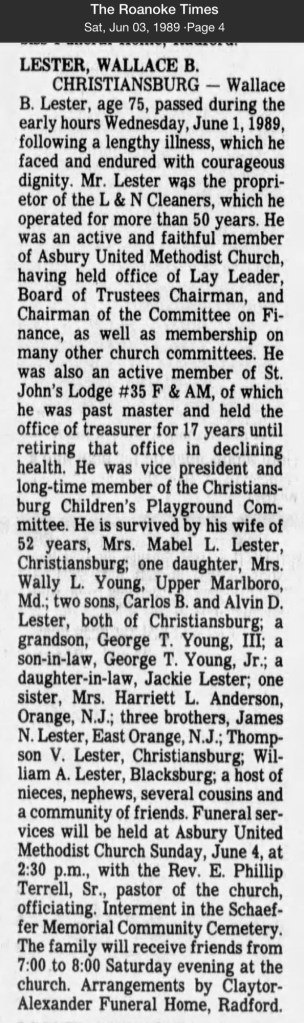

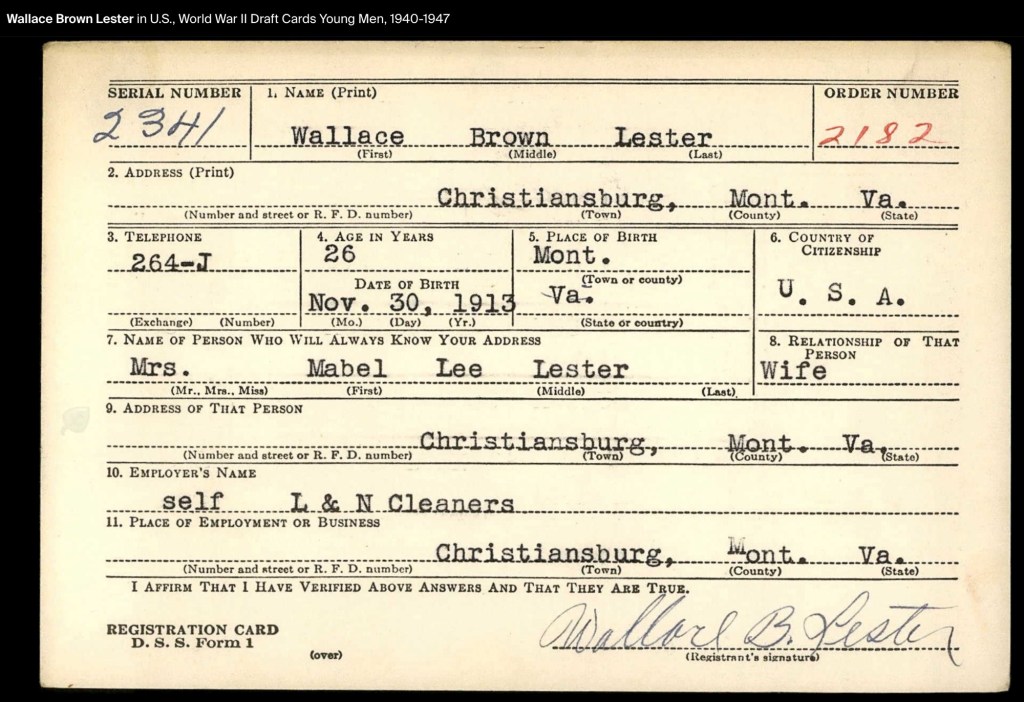

Alvin’s father, Wallace Brown Lester (1913–1989), married Mabel Lee Saunders on June 17, 1937, in Floyd County. The couple lived in Christiansburg, where Wallace owned L&N Cleaners. Alvin’s paternal grandparents were James Niles Wilson Lester (1880–1941) and Fannie Baker Thompson Lester (1886–1987). Fannie was the daughter of Herbert Thompson and Harriett Kincanon. James was the son of John C. Lester (1837–1924) and Annie Pate Lester (1843–1915), both born free in Lunenburg County, Virginia. John C.’s parents were Bolling Lester (1788–?) and Rebecca Barber (1790–1845).

Alvin’s great-uncle, John Wynes Lester (1885–1961), taught, farmed and worked as a carpenter at Christiansburg Institute. He and his wife lived on campus until his death. He is buried in the school’s cemetery.

Luke Valentine, Free Black, Application for Revolutionary War Pension

During the American Revolutionary War, free Black men in Virginia played a meaningful—though often overlooked—role in the fight for independence. From the earliest days of the conflict, free Blacks served in militias, state troops, and Continental units, particularly as manpower shortages grew. Virginia law restricted enslaved people from bearing arms, but free Black men could enlist, serve as substitutes, or be mustered alongside white soldiers, especially in local militia companies.

By the later years of the war, Virginia increasingly relied on these men for defense and campaigns beyond the colony’s borders. Their service included marching long distances, guarding supply lines, engaging Loyalist forces, and fighting in the southern theater, where the war was especially intense in 1780–1781.

Luke Valentine, fifth-great grandfather of Alvin Lester’s, is one such example. He appears on a roster of men led by Captain Adam Clements of Bedford County, Virginia, who marched to South Carolina beginning May 1, 1781. This was a critical moment in the war, as Patriot forces sought to counter British advances in the South. Valentine’s inclusion on this roster places him among the free Black Virginians who answered the call to serve far from home in support of American independence.

After the war, some free Black veterans, including Luke Valentine, applied for Revolutionary War pensions. These applications are vital historical records, offering rare documentation of Black military service and affirming that free Blacks were not only present but active participants in the founding struggle of the United States.