Beatrice Freeman Walker (Interview, courtesy of Virginia Tech University Libraries)

On December 17, 2013, Ms Beatrice Walker provided an oral history for Virginia Tech’s University Special Collections, recorded at the St. Luke, Odd Fellows, and Household of Ruth Hall. Beatrice played a pivotal role in saving the building and is listed as a Trustee on the deed now held by the Town of Blacksburg.

Her interview offers critical insights not found in written records, shedding light on the significant but under-documented role of Maggie Lena Walker’s Independent Order of St. Luke within the African American community of Blacksburg. It also addresses the erasure of the New Town neighborhood driven by corporate greed and the persistence of institutional racism in 21st-century Blacksburg.

Beatrice shared that Mrs. Walker’s mother, Bessie Briggs Freeman, was an active scout for the St. Luke Council, traveling to Richmond and other communities to recruit new members. It is compelling to imagine Bessie collecting, transporting, and depositing membership dues into the St. Luke Penny Bank in Richmond, further linking the local Council to the broader financial and social empowerment network, especially for women, envisioned by Maggie Lena Walker.

Topics per Timestamp (approximate time and the information within brackets are for context and clarification, not provided by the interviewee)

- 00:00 – Introducing Beatrice Freeman Walker: She was born in the region, possibly at Burrell Memorial Hospital in Roanoke. She noted that while Black patients could be treated at Showalter Hospital in Christiansburg, they were not allowed to stay overnight.

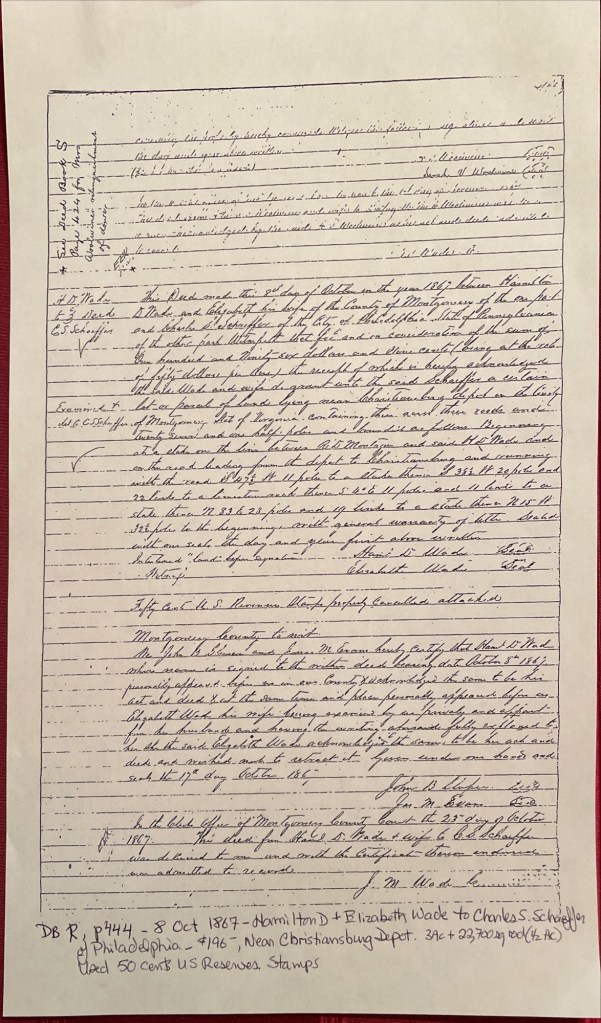

Beatrice grew up with her parents at 202 Jackson Street in a neighborhood known as Jackson. In this area, African American families lived on one side of the street, with their homes facing Jackson Street, while White families lived on the opposite side, facing Penn Street. Black residents also lived on nearby streets, including Bennett, Roanoke, Clay, and Wharton. That was different from New Town which was a totally segregated Black neighborhood on both sides of the street. - 1:45 – The interviewer asked Mrs. Walker how her family came to settle in Blacksburg. She explained that her father [Alonzo Walker, Sr.]was originally from Statesville, North Carolina, but she was unsure of what brought him to Blacksburg. Mrs. Walker mentioned that she believed Black residents were allowed to live on Jackson Street beginning around 1867.

- 1:52 – When asked how her family came to live in Blacksburg, Mrs. Walker explained that her father, Alonzo Freeman Sr., was born in Statesville, North Carolina. He eventually settled in Jacksonville in 1867, establishing roots that led to the family’s connection with the area.

- 3:16 – As noted earlier in the interview, the Jackson and Bennett Street neighborhood was segregated. Mrs. Walker explained that while Black families faced Jackson Street, white families generally faced Penn Street. [he Siebold family had a Jackson Street address but, like the Effinger and Sites families, their homes faced Penn Street.]

In addition to Jackson Street, Black residents also lived on Wharton, Clay, Roanoke, and Lee Streets. While Black and white children often played together, tensions typically arose among the parents. - 5:40 – Children were expected to contribute to their family by helping with chores for their parents and grandparents. Mrs. Walker’s father operated a cleaning business, while her mother, [Bessie Briggs Freeman] worked in private homes, including for Rev. Richardson of the white Episcopal Church located at the corner of Church and Jackson Streets, and for the Red Cross. When a Black parent passed away, her mother coordinated with the Red Cross to bring their soldier child home for the funeral. She also worked for Jim Devine at VPI and was responsible for preparing communion at the Christian and Episcopal Church. [Major General John M. Devine, ret. became Commandant of Cadets in 1952]

- 7:14 – Bessie B. Freeman played a significant role in the Independent Order of St. Luke [specifically with St. Frances Council #235 of Blacksburg] by traveling throughout the region to recruit members for the organization. She journeyed with members from other St. Luke Councils in places like Richmond, South Boston, and Roanoke, who joined her in Blacksburg for these vital recruitment efforts. Mrs. Walker believed her mother and her companions traveled by car.

Mrs. Walker explained that the St. Luke organization was founded by Mary Prout of Baltimore, Maryland, to assist newly freed individuals who were often left to die on roadways or faced significant challenges in securing basic necessities. [The organization provided critical support such as food, clothing, jobs, and life-and-death assistance.]

Mrs. Walker discovered documents belonging to her mother related to St. Luke’s work and gave them to Terry Nichols [Blacksburg Museum]. - 11:15 – She noted, “Most of the people in Blacksburg were St. Luke’s, not Odd Fellows, and that’s why the hall was built.” The St. Luke Council included both men and women, and their meetings were held upstairs in what was considered a sacred space. She also mentioned that the Masons and Eastern Star shared the use of the hall.

- 12:14 – Downstairs, the hall hosted various events to raise funds, including dances, bingo parties, sock hops, weenie roasts, and even “man-only” weddings (held at both the hall and the church). Dinners were also organized to pay for building fund and support members traveling to Convocation in North Carolina or Union meetings in Richmond.

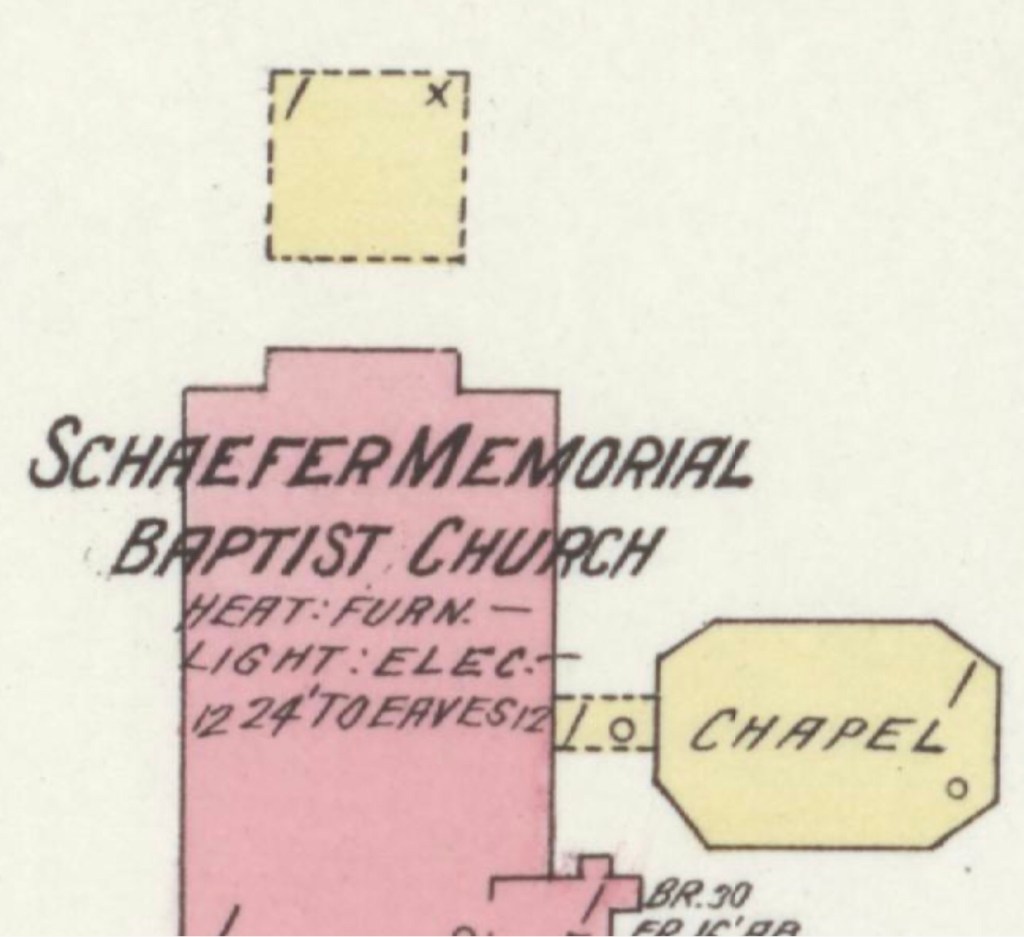

- 14:18 – Mrs. Walker explained that, due to the small African American population in this rural area, the two churches in town—the AME and Baptist churches—collaborated on events such as picnics. Her mother was a member of the First Baptist Church on Clay Street, while her father belonged to St. Paul AME Church on Penn Street. The Baptist church held its services in the evening, while the AME church held morning services, allowing them to attend services at both churches.

- 15:05 – The churches organized picnics at parks in places like Staunton, Natural Bridge, Mill Mountain Star, and Wytheville. On one occasion, their minister, Rev. Archibald Richmond, was arrested during a picnic at the Virginia State Park in Wytheville. The group was asked to move to the Black section of the park, but they refused. As a result, Rev. Richmond was arrested. He was released later the same day by members of the church.

- 17:15 – Another story of resistance involved a bus station sit-in led by Rev. Richmond. At the time, Black people were required to buy their bus tickets at the back door and were not allowed to wait or eat in the station. Rev. Richmond helped lead a sit-in to challenge this discriminatory practice. He also played a key role in integrating the schools. [In Montgomery County, Black children weren’t outright barred from attending high school, but each child had to apply to the school board for permission, often accompanied by a public petition. The bus station was where the Hokie House Bar and Restaurant is now located.]

- 18:35 – Rev. Archie Richmond the leader of the St Paul AME and Rev. Ellison Smyth of the Blacksburg Presbyterian Church were both members of the NAACP in the area. They worked together to challenge local systemic racism, particularly in relation to the segregation of schools and public spaces.

- 19:26 – Mrs Walker was a member of the St Paul AME church.

- 19:45 – “The story of St. Luke’s hasn’t been told enough. All you hear about is the Odd Fellows, but you don’t hear anything about St. Luke’s… that’s the part that’s so interesting, St. Luke’s, because they were the ones who had the insurance.” Mrs. Walker also mentioned, “Maggie L. Walker is the one who created all kinds of opportunities for Black people to learn different trades and jobs.”

Mrs. Walker’s sister, Nannie Bell Walker Snell, attended Bluefield State College for two years but didn’t enjoy it. Instead, she went on to attend Apex Cosmetology School in Richmond, which was part of St. Luke’s initiative to provide job training for women. - 21:45 – Maggie Lena Walker’s vision was, “A penny makes a dollar.” She became the first Black woman to serve as president of a bank. Members of St. Luke’s were required to contribute a minimum of 10 cents. The bank allowed individuals to borrow money to fund their children’s education and also offered life insurance.

“It’s so interesting, but nobody knows about it because it hasn’t been told—like it should be told.”

Mrs. Walker’s mother worked alongside Mr. Carrington from South Boston, who visited the area. Dorothy Turner became the Secretary after Maggie Walker’s death, and Ruth Hilton of Roanoke was also involved. She was busy. [*see information below about these people] - 26:49 – When reflecting on Blacksburg, Mrs. Walker expressed strong feelings about the town’s history. In 1998, the town’s branding was “Blacksburg: A Special Place for 200 Years,” but Mrs. Walker disagreed, stating, “It is not a special place, it is a greedy place.” She continued, “They just took the land from the Blacks. After one Black would leave, Whites take over and would have apartments the next year.”

- 27:36 – “Just like my property was taken when my parents died. Fire department decided they wanted that land and sell or condemn.”

Mrs. Walker explained that her family’s property stretched from Jackson Street to the creek, which made it highly sought after by the town. However, the family was unfairly treated during the sale, especially when they were offered a much lower price than the property’s true value. - 29:20 – The brick house next to the Freemans’ home [Sears family] was moved to Roanoke Street because the family also faced the same treatment.

- 30.00 – Her father owned many pieces of property including Roanoke and a large tract of land known as Paradise View, which stretched from what is now Nellie’s Cave Road (formerly called Grissom Lane) to the area west of Woodland Hills subdivision. It served as a weekend retreat for Black families, offering space to play croquet and badminton, enjoy picnics, and relax. A house on the property was home to a white couple who maintained the grounds and assisted the weekend guests.

She described the beauty of the area, remarking on the abundance of flowering trees throughout the town and the plentiful fruit, including the distinctive Green Gage plums. - 35:00 – Mrs. Walker recalled how segregation did not bother her, though shopkeepers would follow her whenever she entered a white-owned store, reflecting the racial challenges she faced. She worked for Mr. Kidd at Spudnuts Donut Shop, located next to the Lyric Theatre, which later became Carol Lee Donuts. If a white teenage girl spoke with a Black boy, the parents sent their daughter to St Albans, a mental health hospital. Shifting to descriptions of life at the time, she noted that most homes had large gardens, often with chickens and even a cow.

After her father, Alonzo Sr., closed his cleaning business, he went to work for John Warren, the owner of Sanderson’s Cleaners on South Main Street. She mentioned that her father kept a shop ledger, which Lonnie might still have. In his business, he cleaned suits for $2, repaired clothing, and even sold suits that he purchased in Gainsborough.

Mrs. Walker also remembered the skating rink on Airport Road, located next to a seafood restaurant, where dances were regularly held. On Barger Street, there were several Black-owned businesses, including Kip’s Shoe Repair Shop. Kip also owned another shop on the southwest corner of Jackson and Church streets. A Black owned clothes cleaners was located near the VPI cadet dorms. - 45:46 – “Hard to believe that Blacksburg has changed so much,” Mrs. Walker reflected, recalling many landmarks from the 1950s and 60s and comparing them to what she saw in 2013. She mentioned several notable places, including Dr. Roop’s house at the northeast corner of Jackson and Main Streets, Faculty Row, and the houses along North Main Street. She also remembered Mr. Sears’ barber shop, which was located to the right of the Lyric Theatre and later became Carol Lee Donuts. Other landmarks included Kip Wade’s shoe repair shop on Jackson Street, and Lewis [?] who ran a cleaners on the south side of East Roanoke Street near Woolwine.

Families from that same neighborhood included the Pages, Warrens, Carrolls, Saunders, Colemans, and the Taylors from West Virginia, along with Chip Price, who provided taxi service. She also recalled the Clay Street dance hall, the Moon Glow, and Laura Anderson, who was 106 years old in 1976 and the oldest person in the county at that time. - 55:32 – In this part of the interview, Mrs. Walker recounted how the building was saved when someone brought the Town engineers’ condemnation notice to the public’s attention, sparking community action to preserve the structure. Christine Price, Ethyl Dobyns, and Mrs. Walker were all involved in the effort.

- 1:00:43 – The hall has always been in use and never left unattended. Mr. Price, a local contractor, stored lumber in the hall, and later a woodworker converted the space into a workshop. In exchange for maintaining the building, these men were allowed to utilize it rent-free. However, when Mr. Price was overseeing the building, Mrs. Dobyns discovered that the original framed charter, pictures, chairs, and documents were scattered on the second floor, and several items, including one of the podiums, were missing.

- 1:05:38 – The interviewer asked if desegregation brought any changes to the St. Luke and Odd Fellows organizations in Blacksburg. Mrs. Walker was emphatic in her response, stating that there was no change to the organization, implying that racial attitudes had not shifted. She noted that some of the Museum’s pamphlet was problematic.

- 1:10:13 – Mr. Floyd Hobeson Meade trained a turkey to gobble every time the VPI football team scored a goal. Mrs. Walker mentioned his death in 1941 after he was struck by a car on Airport Road. Tragically, he died because the local hospital refused to treat Black patients, forcing Meade to be transported to Jefferson Hospital, which delayed his care and put him in greater peril.

- 1:15:34 – The discussion turned to the segregation of the local theater, the Lyric. Mrs. Walker described how Black patrons were required to use a separate entrance that led to a designated balcony, highlighting the racial divisions that were enforced even in entertainment spaces.

- 1:20:00 – Mrs. Walker was the youngest of four siblings, one of two girls alongside three brothers. Two of her siblings, Alonzo and Nannie Bell, attended the segregated Lucy Addison High School in Roanoke. Each Sunday afternoon, the family would visit their aunt in Roanoke, where Alonzo and Nannie Bell stayed during the school week. They returned home on Fridays to spend the weekend with the family. Alonzo became the principal of the Clay Street grade school.

- 1:21:44 – Beatrice Freeman, Mrs. Walker’s mother, operated an ice cream parlor in a shop attached to their home, located just north of the house near the stream. Later, this shop was repurposed as a beauty salon run by Nannie Bell, Mrs. Walker’s older sister. Nannie Bell had trained at the renowned Apex Beauty School in Richmond.

- 1:23:14 – Mrs. Walker attended the segregated Clay Street Grade School and was surprised to learn that the Blacksburg Museum was unaware of its history. She recalled how parents had to raise funds to purchase a heating furnace, as the local public school board failed to provide one—a basic necessity one might expect from a public institution. The school consisted of two rooms divided by a sliding door, allowing the space to accommodate both lower and upper grades. Two teachers taught the students, and a small kitchen was located at the back of the building.

- 1:27:00 – The St. Luke regalia included a distinctive hat that newly initiated members were required to purchase within 90 days of joining.

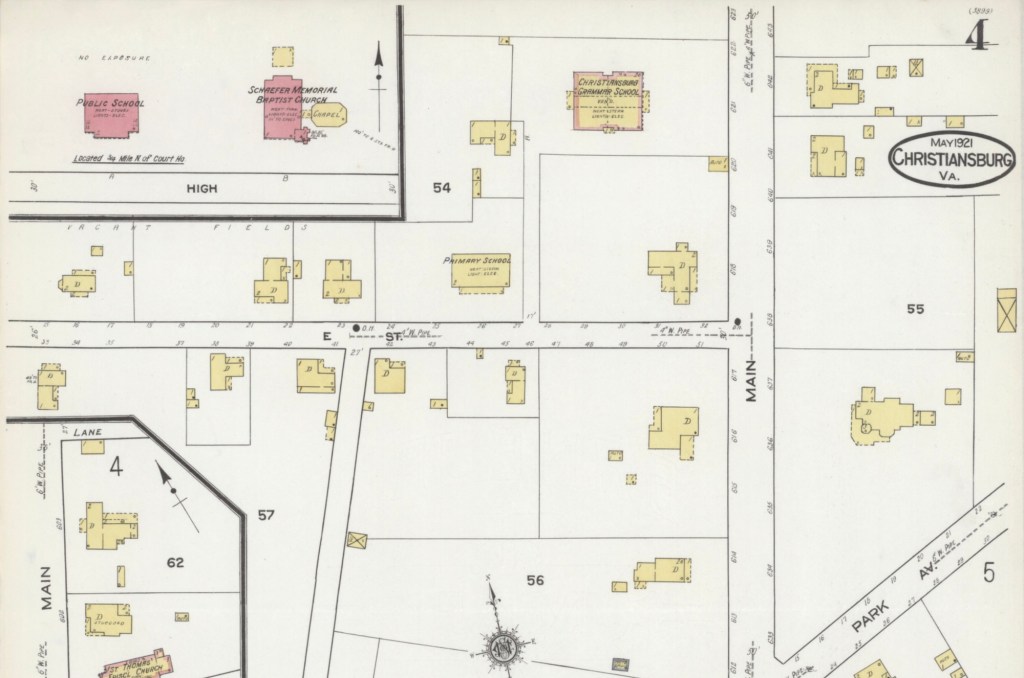

- 1:28:02 – Christiansburg Institute welcomed students from as far away as New York, Philadelphia, and Martinsville. However, Mrs. Walker and her siblings attended as day students, commuting daily by taxi.

- 1:33:50 – Mrs Walker’s brother, Alonzo attended Bluefield State.

- 1:36:10 – In 1943, during her senior year at Christiansburg Institute in Cambria—a regional African American high school serving Montgomery County, Radford, Pulaski, and Giles, with both boarding and day students—Mrs. Walker took the U.S. Civil Service exam. Upon passing, she accepted a job in Washington, D.C. in 1945. Her older sister, Nannie Bell, also worked in Washington as a coder. Prior to this, Mrs. Walker had attended business school in Roanoke after attending West Virginia State for a short time.

- 1:41:57 – Nettie Anderson, daughter of Laura Anderson, was principal at the Clay Street grade school for African Americans.

- 1:46:04 – Irving Peddrew III boarding with William and Jannie Hoge, Town racism.

- 1:50:34 – Mrs. Walker explained why many children of Black families left the area in search of quality employment opportunities, noting that local jobs were often preferentially given to family members. She mentioned knowing Charlie L. Yates at VPI and described the various jobs she held in Blacksburg. Among these was her connection to the Tutwiler Hotel and Boarding House. Mrs. Walker’s children included Leo, William, and Delores.

- 1:52:22 – The interviewer asked Mrs. Walker if she was familiar with the Montgomery and Pulaski Education Welfare Association, a Black organization active in 1948 that registered Black voters, including Warren Carroll. Mrs. Walker acknowledged that she was aware of the organization but was not personally involved.

- 1:54:00 – The topic of Friendship Gardens, promoted by the local Black Garden Club, was discussed. Mrs. Walker was familiar with the initiative but did not participate.

- 1:58:11 – The conversation shifted to the election of President Obama and the racism that surfaced across the nation during this historic event.

- For the remainder of the recording, the interviewer asked Mrs. Walker if there was anything else she wanted to add. She expressed her concern that the history of St. Luke was excluded from the narrative presented by the Museum committee, which unsettled her. Over time, St. Luke was incorporated into the name of the hall alongside the Odd Fellows, but only after Mrs. Walker pushed back against Terry Nichols. She stressed that St. Luke was vital to the local African American community, so much so that its members performed ceremonial rites at funerals for their fellow members.

Notes of Context

In the interview Mrs Walker mentions three people who worked with her mother (time stamp 21:45). Mr J.S. Carrington is mentioned in the National Park Service Finding Aid, page 32, Series III: Insurance, subseries A: Deputy Commissions and Assignments, Box 04, for 1943, 1948, 1950. He was also listed on page 39, Box 07, Folder 34 under death claim investigations, 1956.

Dorothy V. Turner is mentioned on the same page, 1966.