“Stripped to the waist and bound to a tree…” Lexington Gazette, page 1, April 23, 1904

Content Warning

This page contains descriptions of racial violence, including abduction, torture, and threats of lynching. The language quoted from historical sources reflects the racist ideology of the time and is presented for the purpose of documentation and interpretation, not endorsement. Note that “lynching” is defined by the Emmett Till Antilynching Act of 2021. Readers are encouraged to proceed with care.

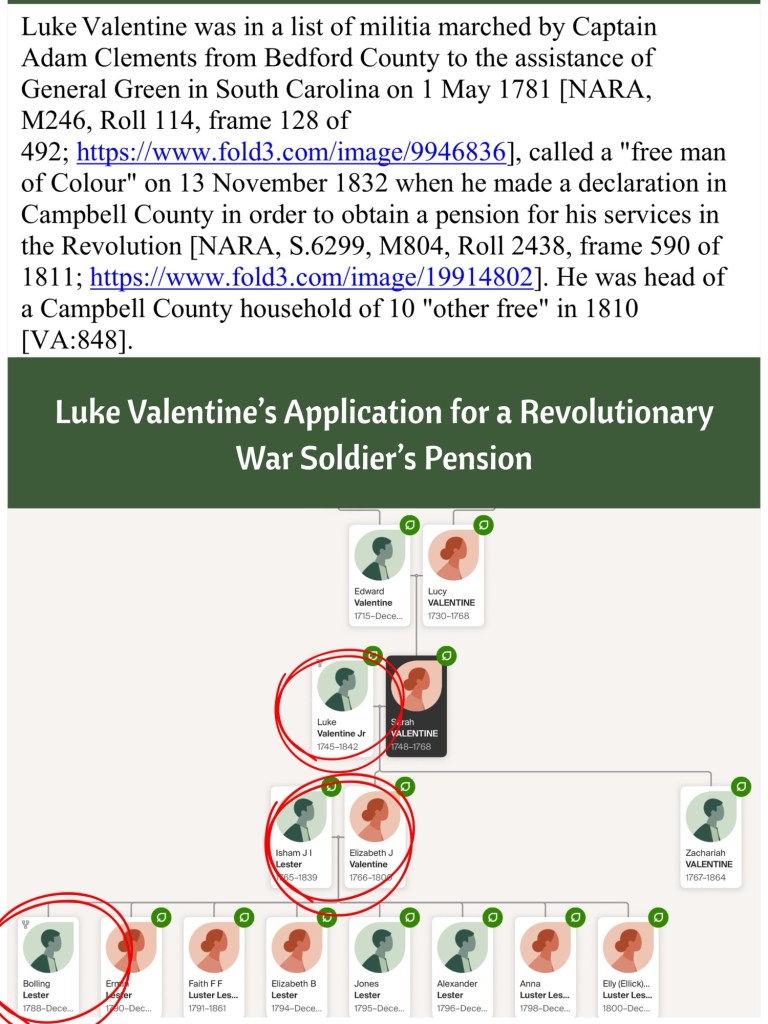

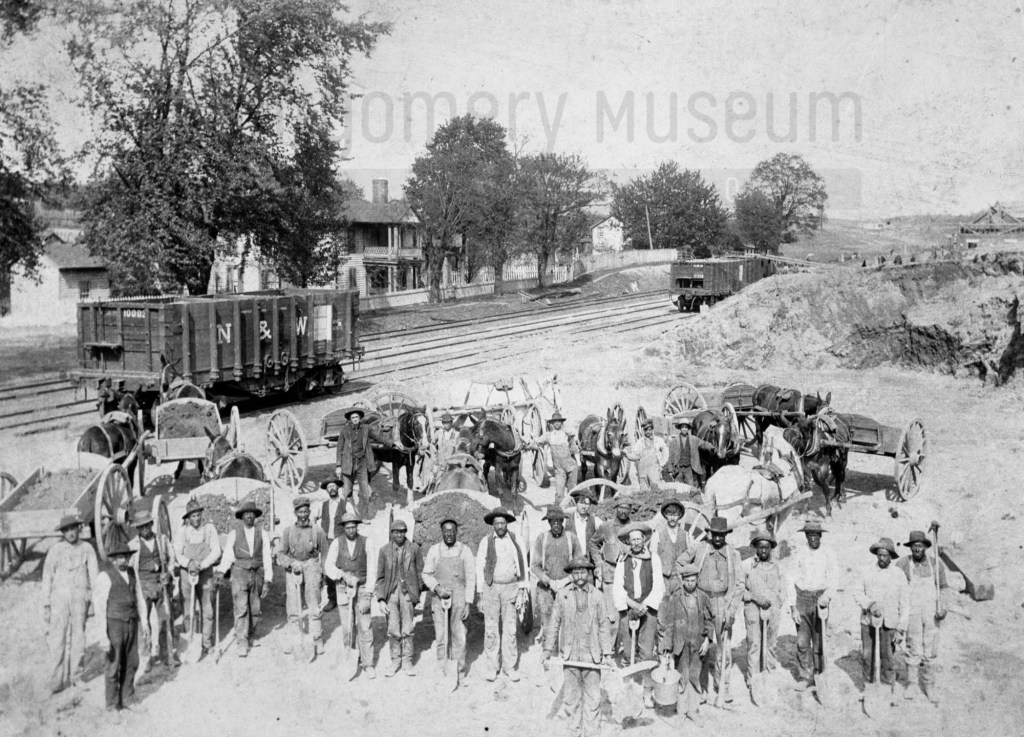

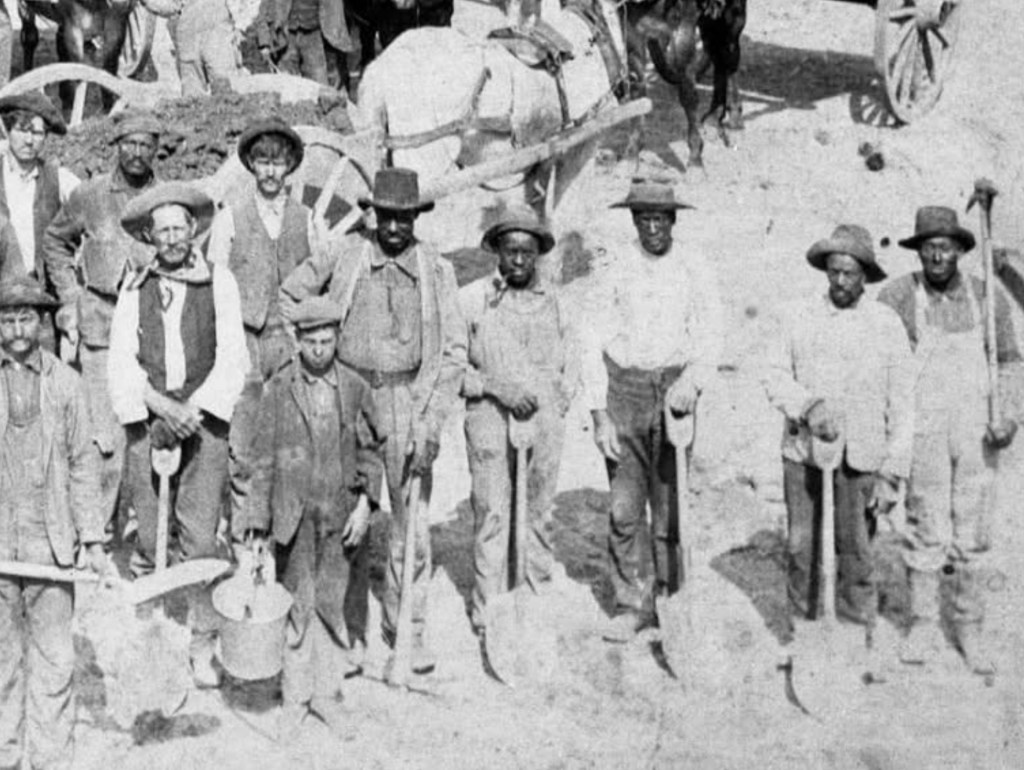

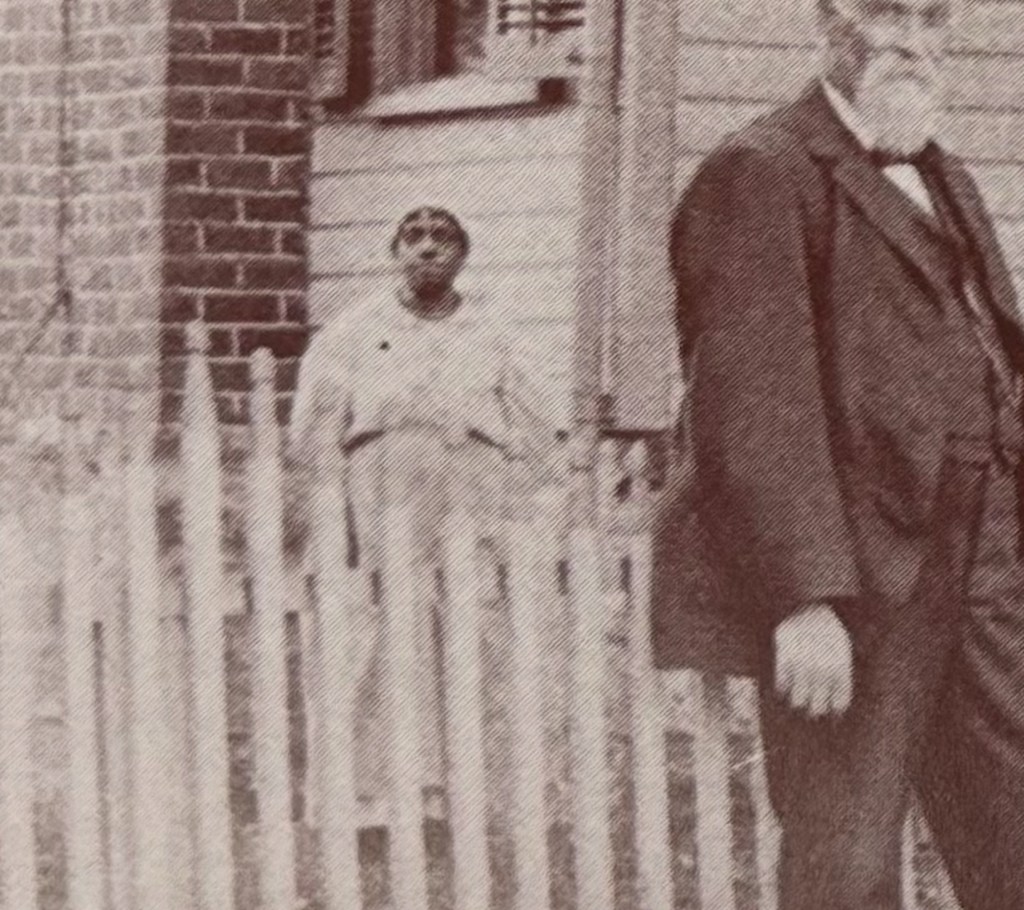

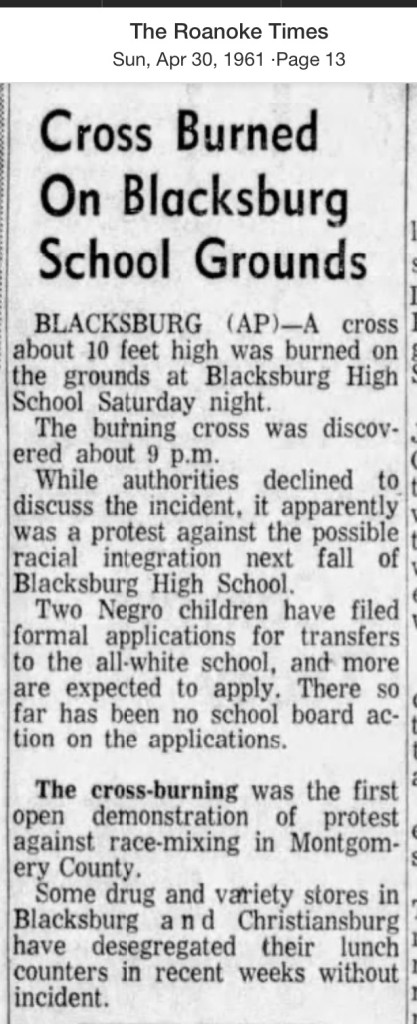

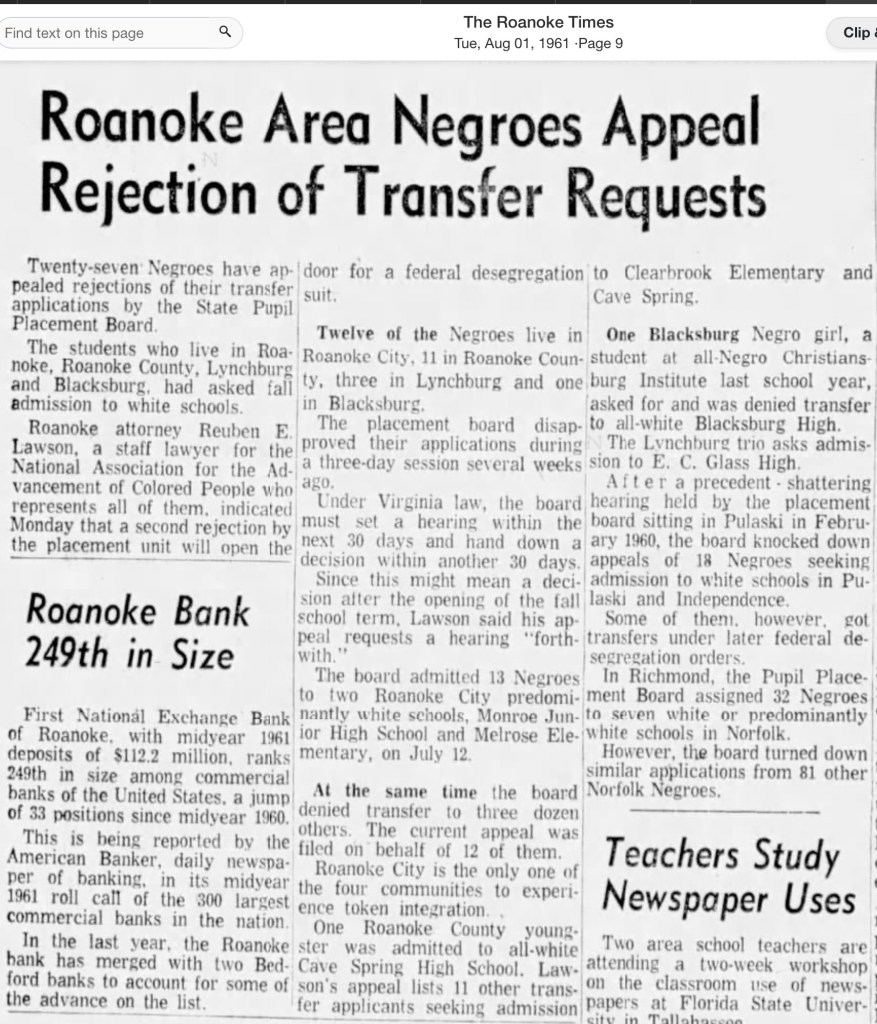

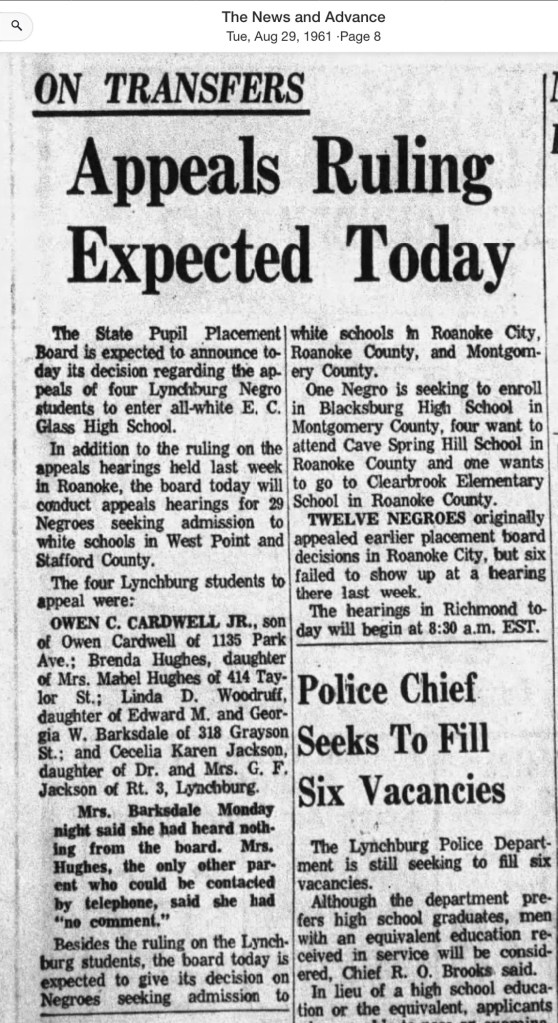

On April 20, 1904, an African American man identified only as Alexander was abducted, tortured, and nearly killed by cadets from Virginia Polytechnic Institute (then V.P.I.) in Blacksburg, Virginia. The attack was not hidden or denied. It was publicly described and justified in a first-person letter written by a cadet and published in The Roanoke Times on April 23, 1904.

The letter recounts how V.P.I. cadets organized, detained Alexander without legal process, removed him from town limits, tied him to a post, and beat him for approximately forty-five minutes. The author explicitly frames the violence as a “lesson” meant to terrorize Black residents and enforce white supremacy under the pretext of protecting white women. Though lynching was discussed among the attackers, Alexander survived and was forced to flee the area under threat of death if he returned.

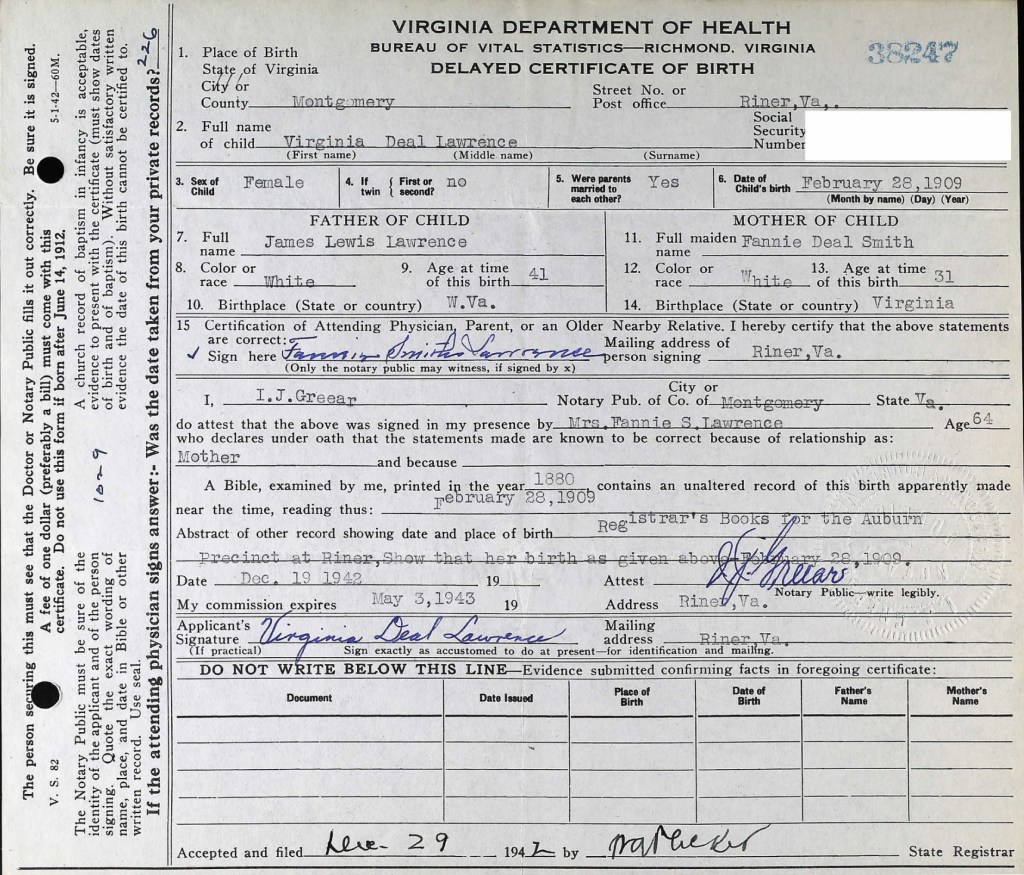

We do not know Alexander’s full name or what ultimately happened to him. “Alexander” is the only name recorded, but the letter states that he lived in Blacksburg and had family there. The absence of fuller identification reflects a broader pattern in the historical record, where Black victims of racial terror were often deliberately anonymized while their attackers were named, defended, and celebrated.

The letter was authored by R. S. Royer, a V.P.I. student from Roanoke who was 19 years old at the time and a member of the Class of 1905. Royer later served as president of the German Club, editor-in-chief of The Bugle yearbook, and sergeant-at-arms for his class. Though a junior at the time of the attack, his language and position suggest leadership and ideological commitment to the violence he described.

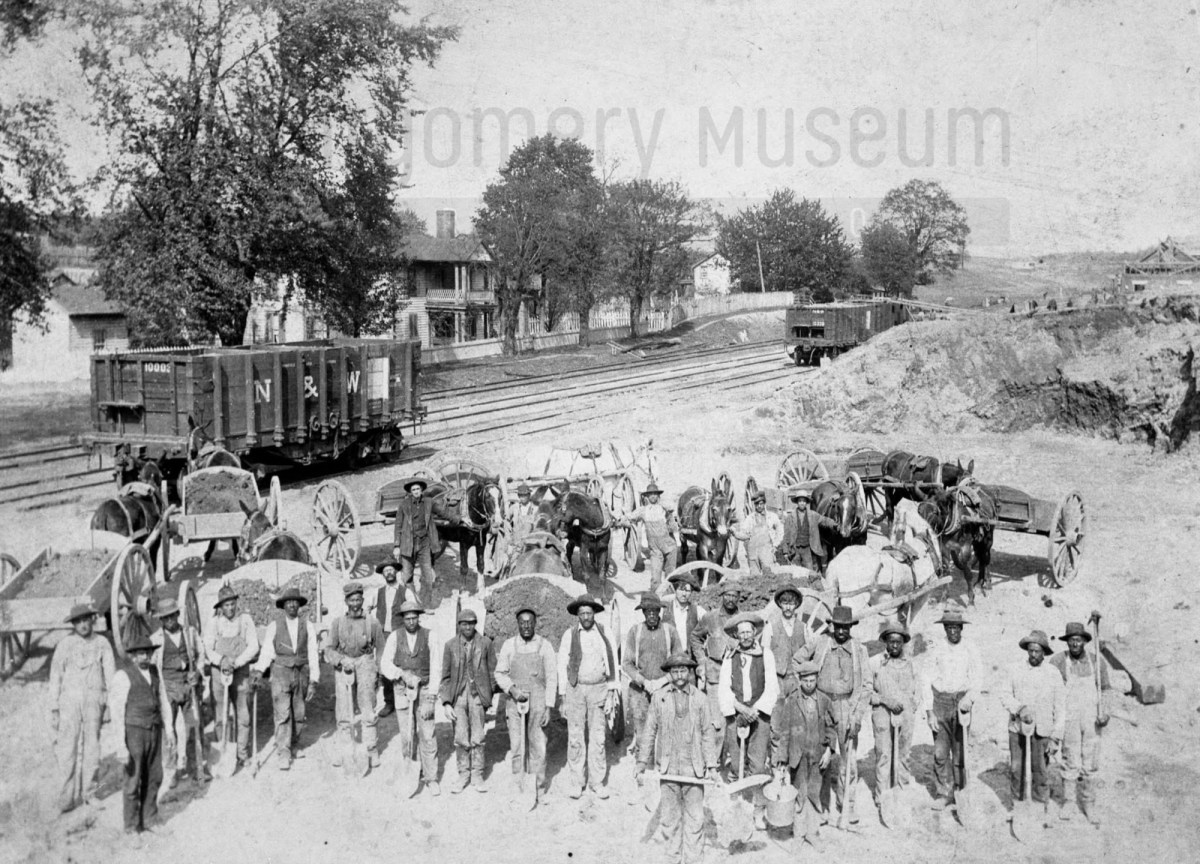

This account is preserved here not to repeat its justifications, but to confront them. The 1904 attack on Alexander was an act of racial terror carried out by young men acting with confidence, coordination, and impunity. Remembering this event is essential to understanding the lived reality of Black life in Blacksburg at the turn of the twentieth century—and the institutional and communal forces that enabled such violence to occur without consequence.

Help Us Remember Alexander

We do not know Alexander’s full name, age, occupation, or what became of him after he was forced to leave Blacksburg. His partial anonymity reflects a painful truth: Black victims of racial terror were often left unnamed in the historical record, while their attackers were identified and defended.

We invite community members, descendants, researchers, and local historians to help us recover more information about Alexander and the Black community of Blacksburg in the early twentieth century. Family records, oral histories, church records, cemetery information, or other sources may hold pieces of this story.

If you have information or would like to assist with research, please contact us. Remembering Alexander is an act of historical justice.

Historical Note: Contemporary newspapers described the 1904 attack on Alexander as a “whipping,” a term that minimizes what occurred. Alexander was abducted by a mob, taken out of town, tied to a post, beaten for nearly an hour, and threatened with death if he returned.The attackers discussed lynching during the assault. Although Alexander survived, historians recognize this violence as part of the broader system of lynching and racial terror used to intimidate Black communities and enforce white supremacy.

Newspaper Accounts and Transcriptions

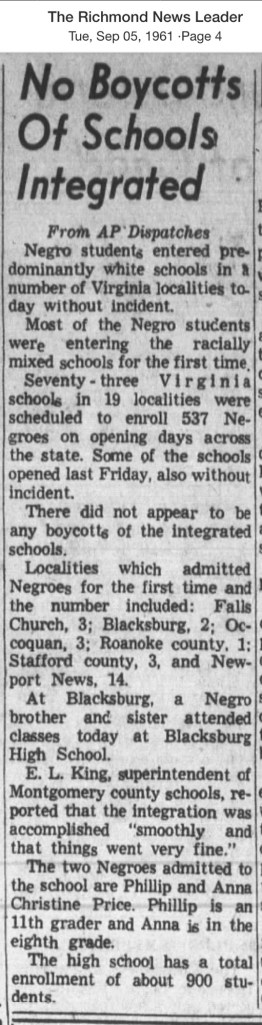

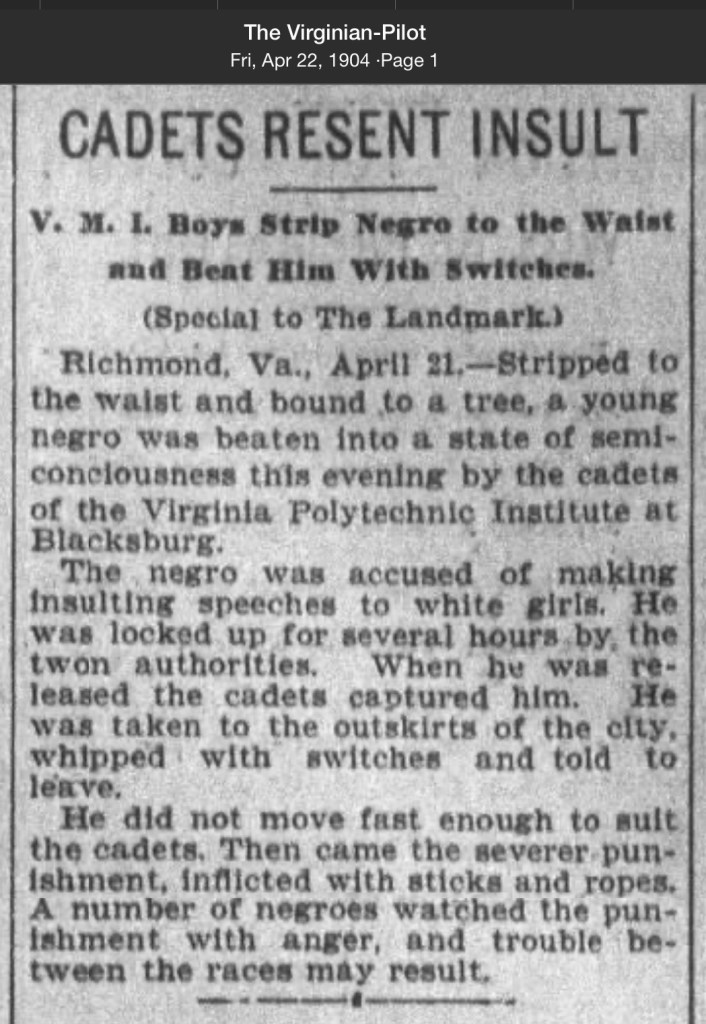

Virginian-Pilot, Fri, April 22, 1904, page 1:

Cadets Resent Insult

Richmond, Va., Stripped to the waist and bound to a tree, a young Negro was beaten into a state of semi consciousness this evening by the cadets of the Virginia polytechnic Institute at Blacksburg.

The Negro was accused of making insulting speeches to white girls. He was locked up for several hours by the town authorities. When he was released, the cadets captured him. He was taken to the outskirts of the city, whipped the switches and told to leave.

He did not move fast enough to suit the cadets. Then came the severe punishment, inflicted with sticks and ropes. A number of Negroes watched the punishment with anger, and trouble between the races may result.

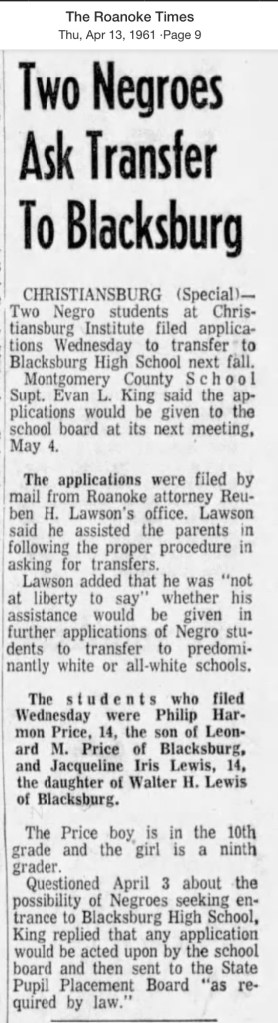

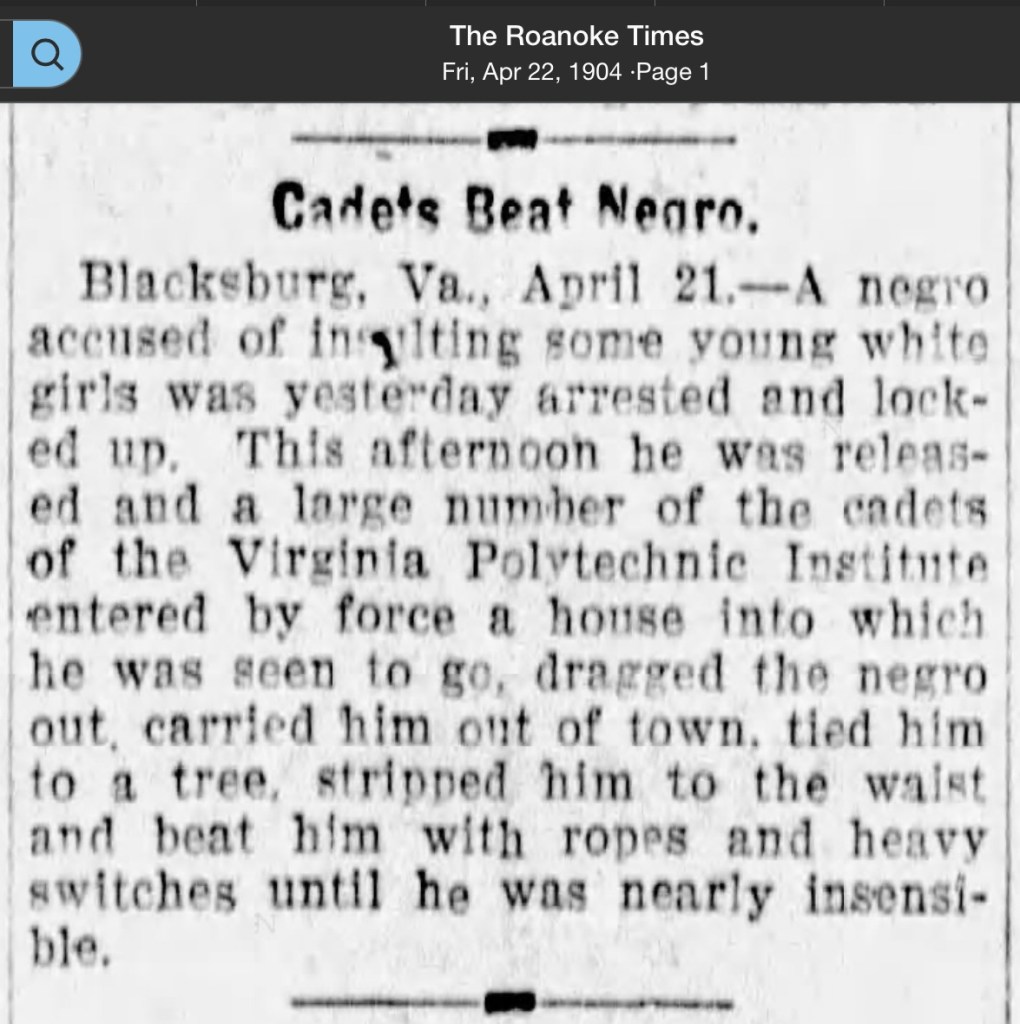

The Roanoke Times, Fri, April 22, 1904, page 1:

Cadets Beat Negro

Blacksburg, Va., April 21. A Negro accused of insulting some young white girls was yesterday arrested and locked up this afternoon. He was released and a large number of the cadets of the Virginia polite Institute entered by force a house into which he was seen to go, drag the Negro out, carried him out of town, tied him to a tree, stripped him to the waist and beat him with ropes and heavy switches until he was nearly insensible.

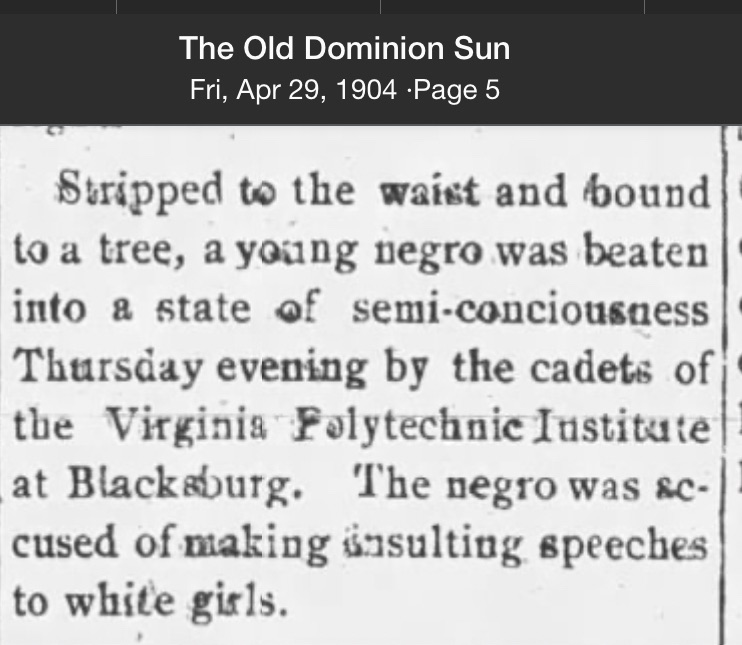

The old Dominion Sun, Fri, April 29, 1904, Page 5: Stripped to the waist and bound to a tree, a young Negro was beaten into a state of semi consciousness Thursday evening by the cadets of Virginia Virginia Tech Institute at Blacksburg. The Negro was accused of making insulting speeches to white girls.

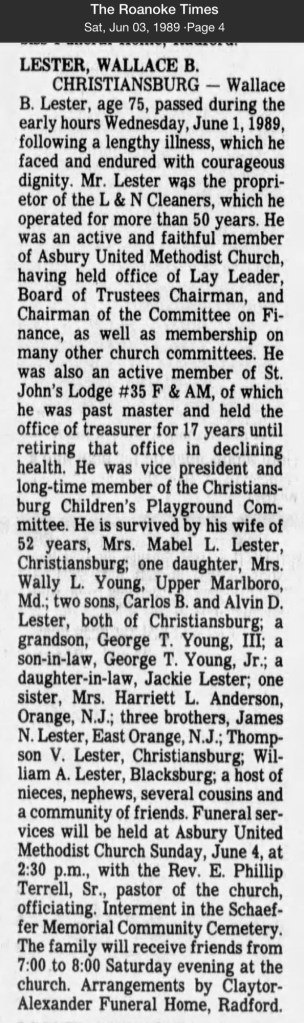

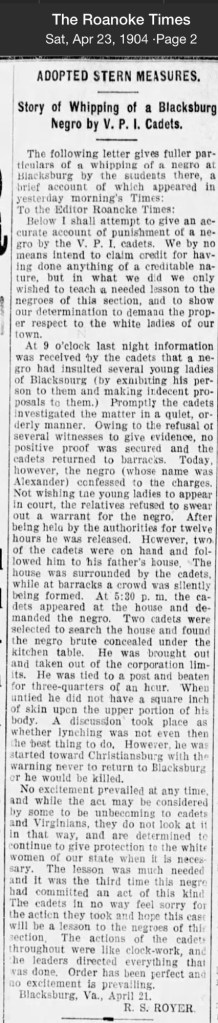

The Roanoke Times, Sat, April 23, 1904, page 2:

Adopted Stern Measures

Story of Whipping of a Blacksburg Negro by V.P.I. Cadets The following letter gives fuller particulars of a whipping of a Negro at Blacksburg by the students there, a brief account of which appeared in yesterday mornings times:

To the editor, Roanoke Times:

Below, I shall attempt to give an accurate account of punishment of a Negro by the VPI cadets. We by no means intend to claim credit for having done anything of a credible nature, but in what we did, we only wish to teach a needed lesson to the Negroes of this section, and to show our determination to demand the proper respect to the white ladies of our town.

At 9 o’clock last night information was received by the cadets that a Negro had insulted several young ladies of Blacksburg ( by exhibiting his person to them and making indecent proposals to them.) Promptly, the cadets investigated the matter in a quiet, orderly manner. Owing to the refusal of several witnesses to give evidence, no positive proof was secured, and the cadets returned to barracks. Today, however, the Negro (whose name was Alexander) confessed to the charges. Not wishing the young ladies to appear in court the relatives refused to swear out a warrant for the Negro. After being held by the authorities for 12 hours, he was released. However, two of the cadets were on hand and followed him to his father‘s house. The house was surrounded by the cadets, while at barracks, a crowd was silently being formed. At 5:30 PM, the cadets appeared at the house and demanded the Negro. Two cadets were selected to search the house and found the Negro brute concealed under the kitchen table. He was brought out and taken out of the corporation limits. He was tied to a post and beaten for 3/4 of an hour. When untied he did not have a square inch of skin upon the upper portion of his body. A discussion took place at whether lynching was not even then the best thing to do. However, he was started towards Christiansburg with a warning never to return to Blacksburg where he would be killed.

No excitement prevailed at any time, and while the act may be considered by some to be unbecoming to cadets, and Virginia‘s, they do not look at it in that way, and are determined to continue to give protection to the white women of our state when it is necessary. The lesson was much needed, and it was the third time this Negro had committed an act of this kind. The cadets in no way feel sorry for the action they took and hope this case will be a lesson to the Negroes of the section. The action of the cadets throughout were like clock-work, and the leaders directed everything that was done. Order has been perfect and no excitement is prevailing. Blacksburg, Virginia, April 21. R.S.Royer

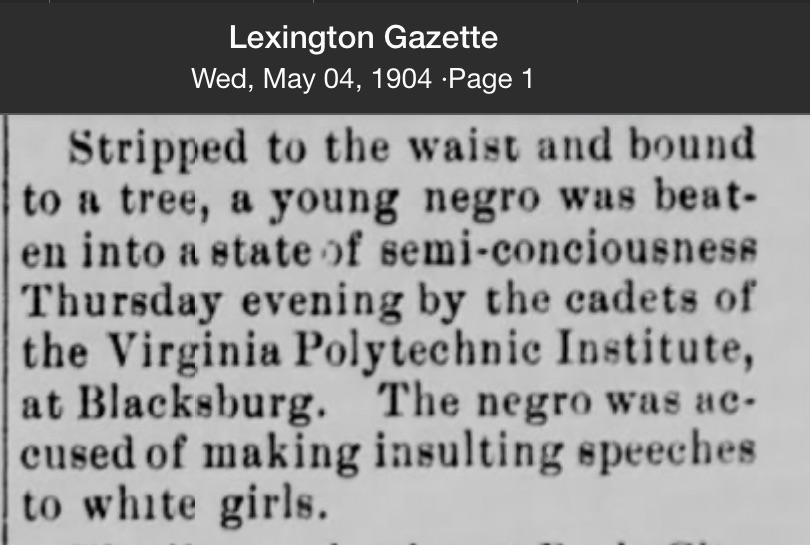

Lexington Gazette, Wed, May 04, 1904, page 1.

stripped to the waist and bound to a tree, a young Negro was beaten into a state of semi consciousness Thursday evening by the cadets of the Virginia polytechnic Institute, at Blacksburg. The Negro was accused of making insulting speeches to white girls.