When Virginia’s earliest European colonial settlers first pushed westward beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains, they entered the border lands already inhabited by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. As Europeans laid claim to these territories in the 18th century, Virginia’s county boundaries began shifting rapidly to keep pace and the need for local governance.

At first, all of western Virginia was considered part of vast counties based far to the east. Augusta County, created in 1738, stretched from the Blue Ridge to the Mississippi River—a landmass so large it was nearly impossible to govern effectively. As settlement expanded, Augusta was gradually carved into smaller counties.

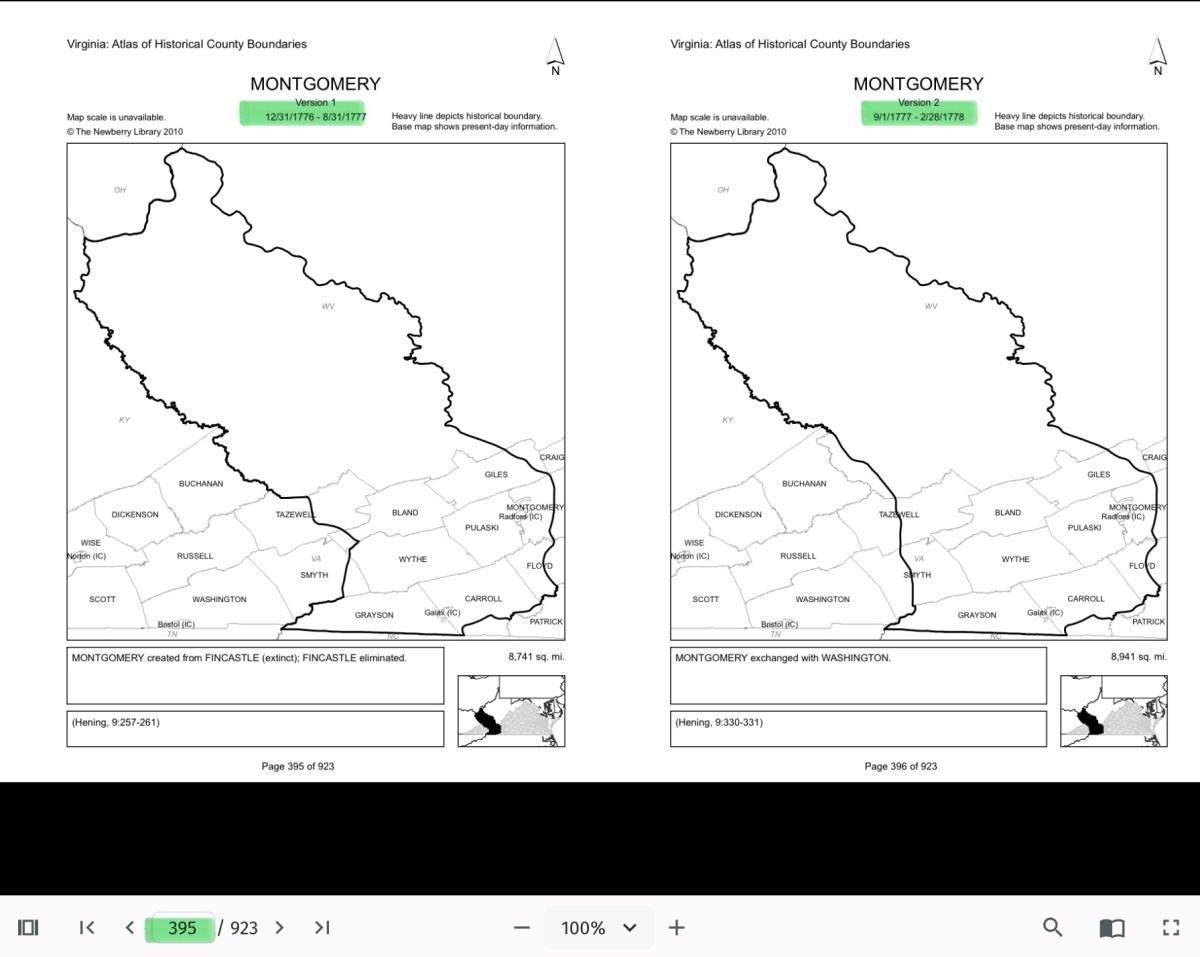

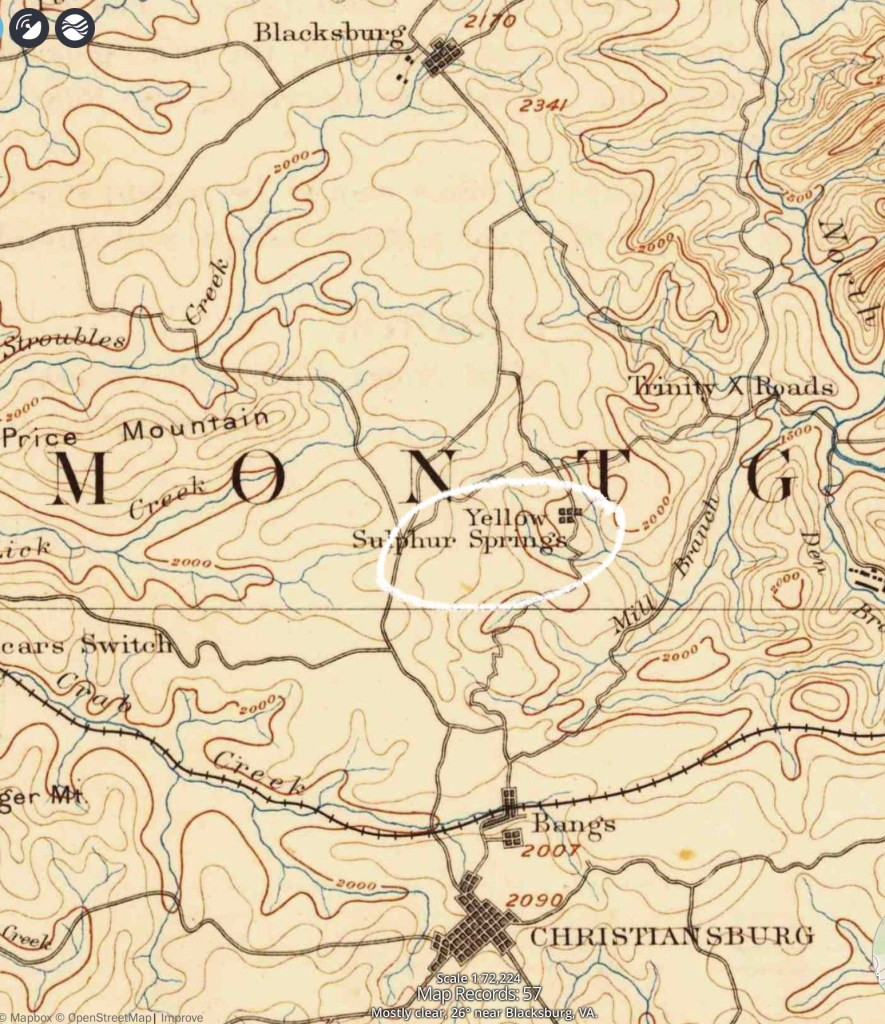

Botetourt County was created in 1770 out of Augusta, and just two years later, in 1772, Fincastle County was formed to cover the far southwest. But Fincastle itself was short-lived: in 1776, it was split into three new counties—Montgomery, Washington, and Kentucky (the latter eventually becoming the Commonwealth of Kentucky).

Thus, Montgomery County was officially established in 1776, named in honor of General Richard Montgomery, a Revolutionary War hero.

Like most early counties, Montgomery did not remain the same size for long. As population grew and communities demanded closer courts and local representation, Montgomery’s original boundaries were gradually reduced.

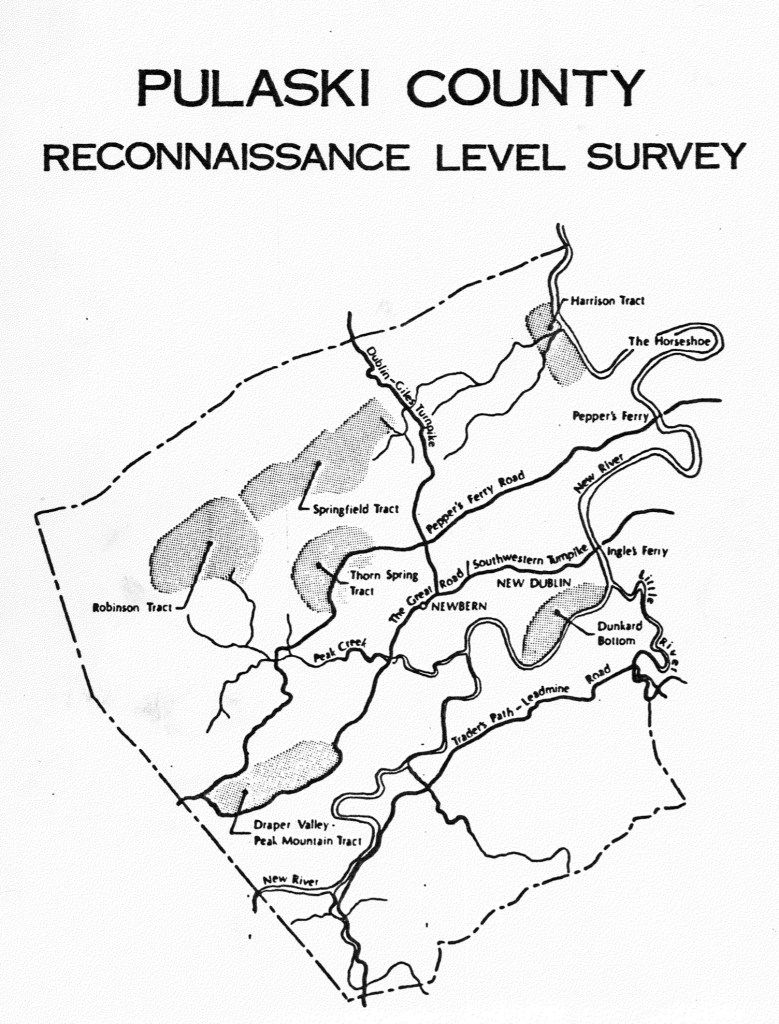

1790: Wythe County was formed from Montgomery. 1790: Parts of Montgomery contributed to the creation of Kanawha County (now in West Virginia). 1806: Giles County was carved from Montgomery, Monroe, Wythe, and Tazewell. 1806–1830s: Additional shifts continued, with Montgomery giving land to Floyd (1831), Pulaski (1839), and others.

By the mid-19th century, Montgomery County had taken on the approximate shape we recognize today.

Why this matters

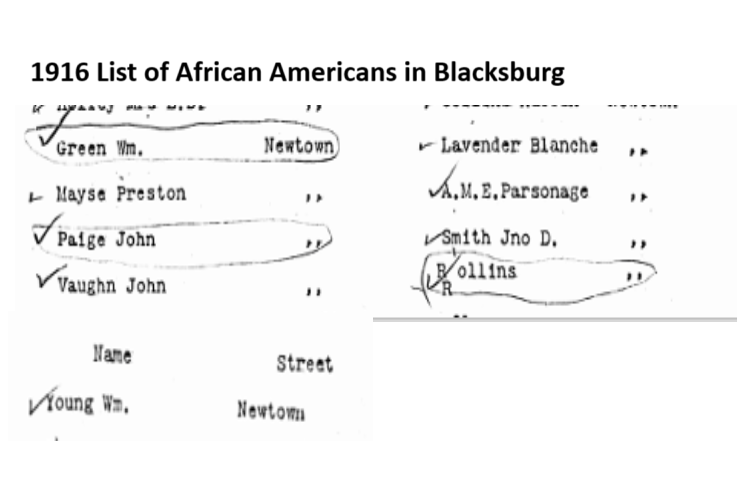

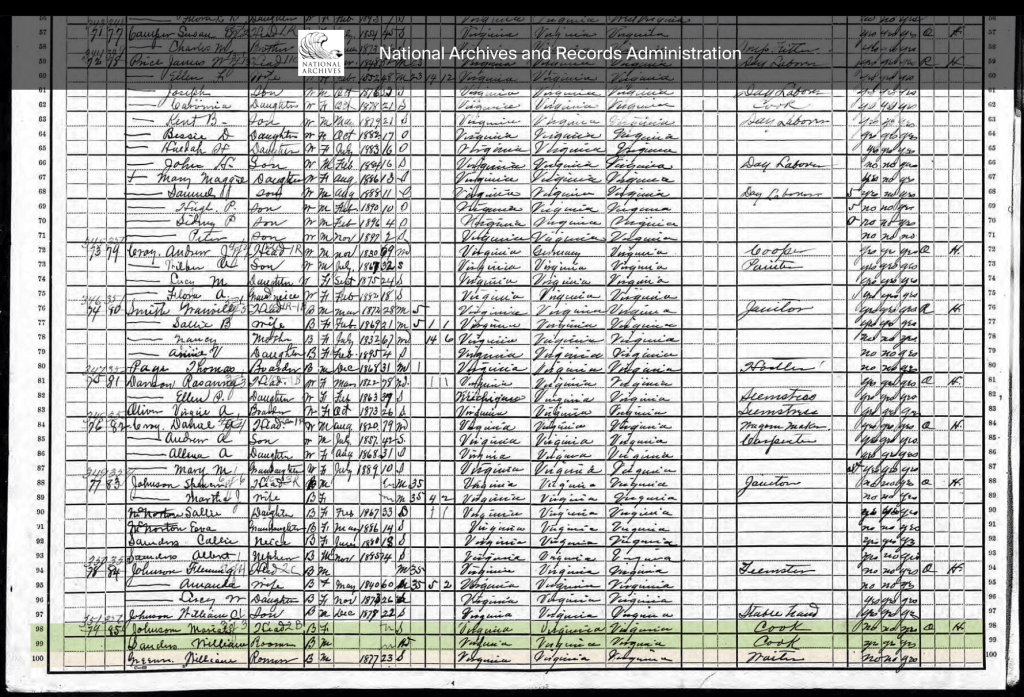

Tracing these changing boundaries shows how the western border lands of Virginia evolved from a vast Indigenous landscape into the network of counties we know today. When we study Montgomery County’s formation and its changing borders, we are not only tracking political geography—we’re also uncovering how those shifts shaped the daily realities of enslaved people and freedmen. The “line on a map” often meant the difference between where families were recorded, where they could live, and how they could begin to claim freedom and opportunity.

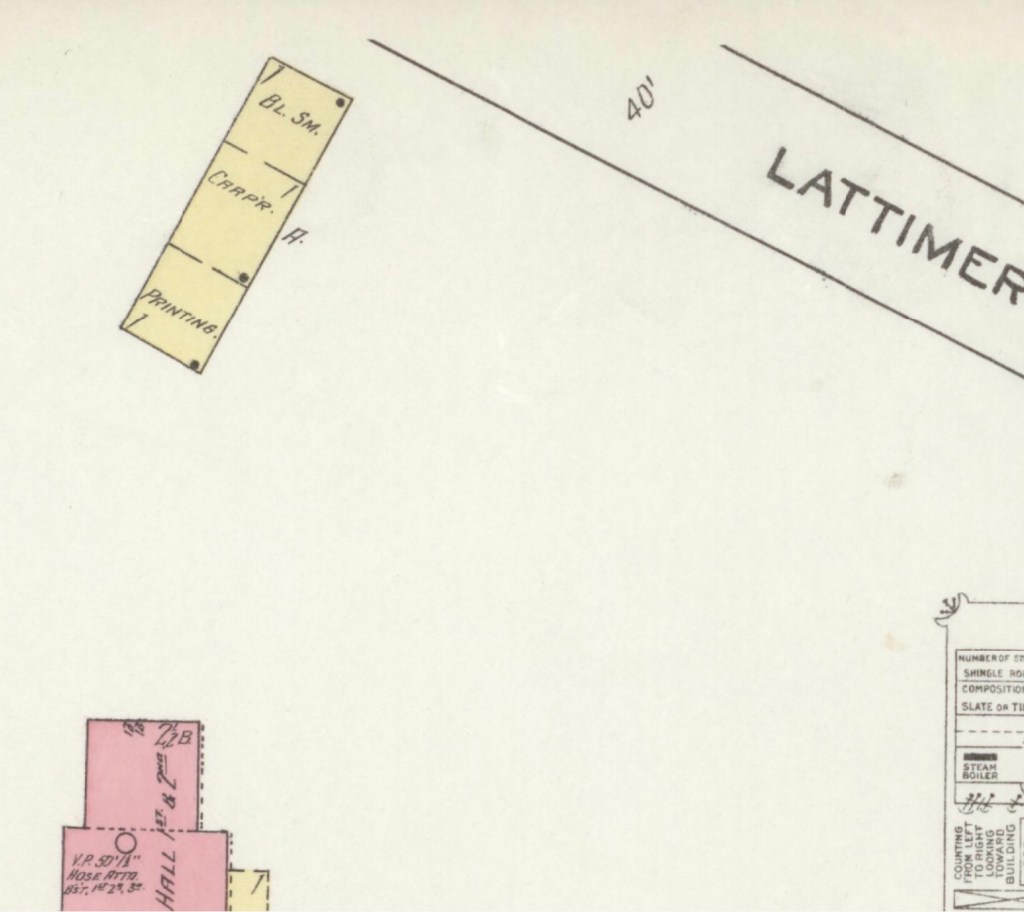

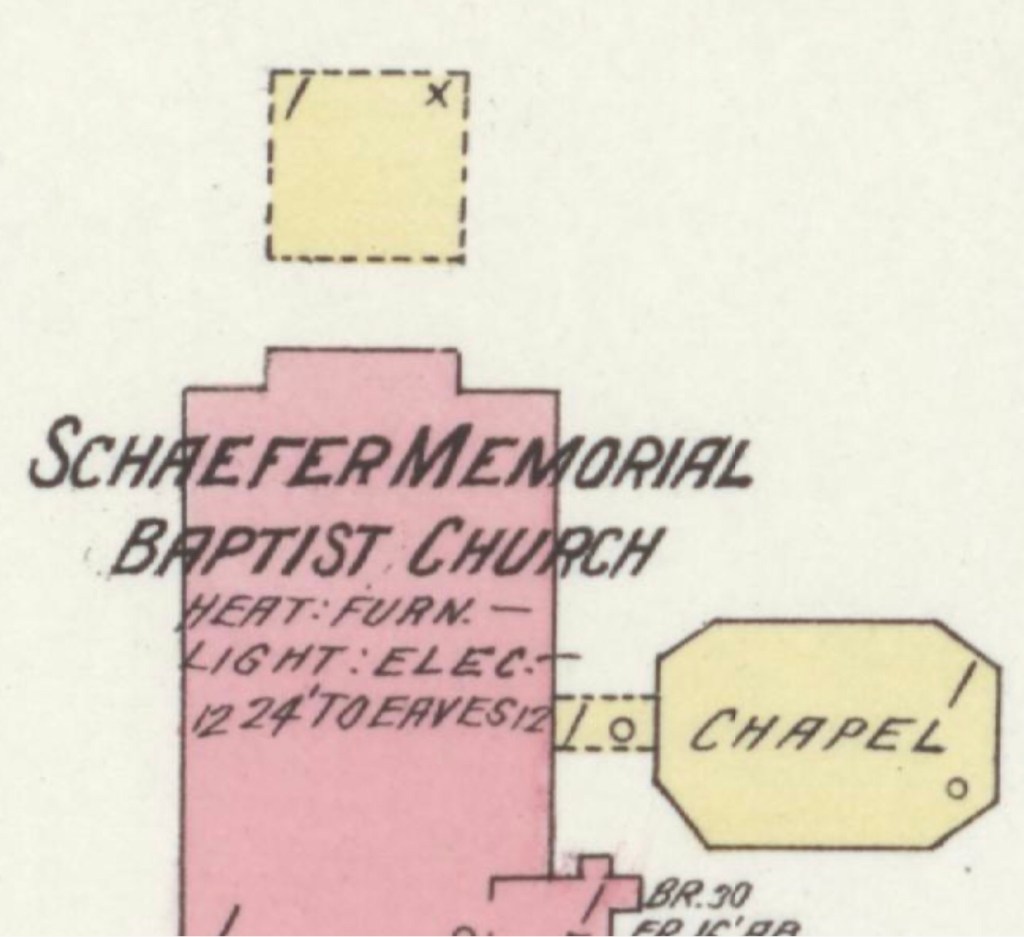

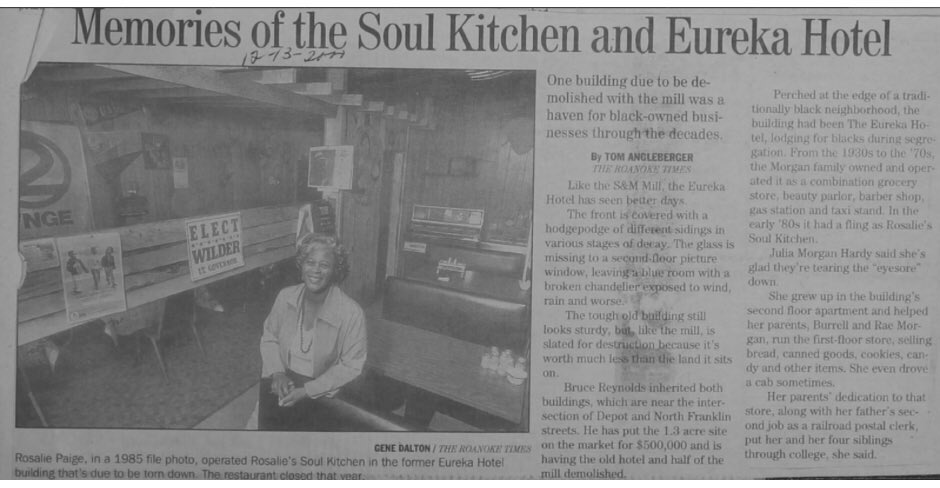

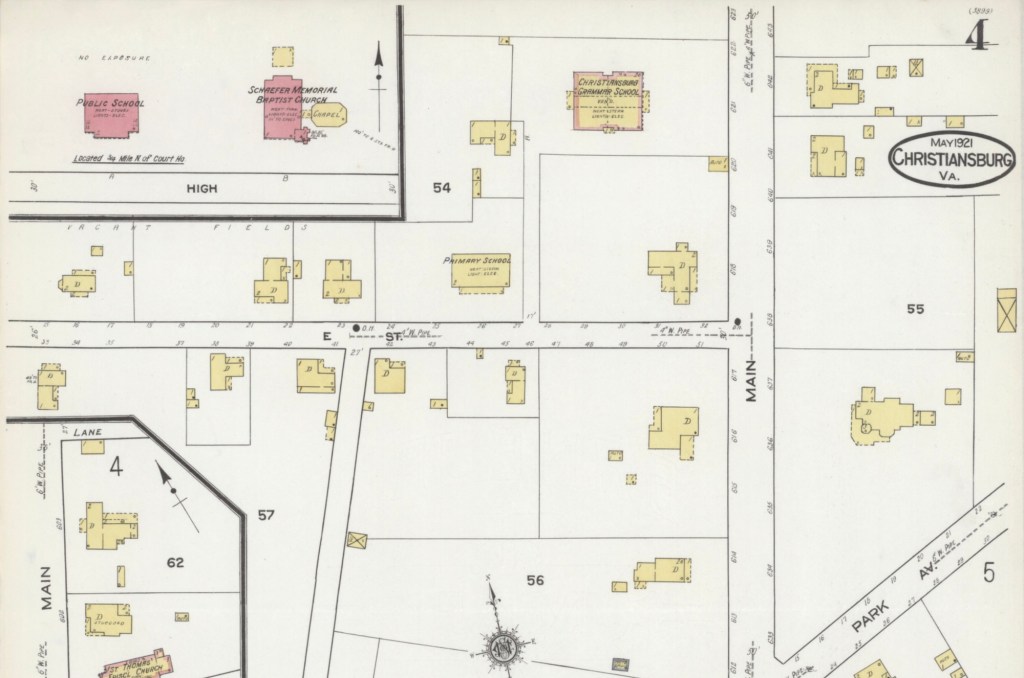

County seats like Christiansburg were not only centers of trade and government but also the location of the slave market and the courthouse records that tracked the lives of enslaved people. After emancipation, those same courts became the places where freedmen registered marriages, secured contracts, and sought land. As county lines shifted, so too did the jurisdictions that controlled access to justice, opportunity, and community life.

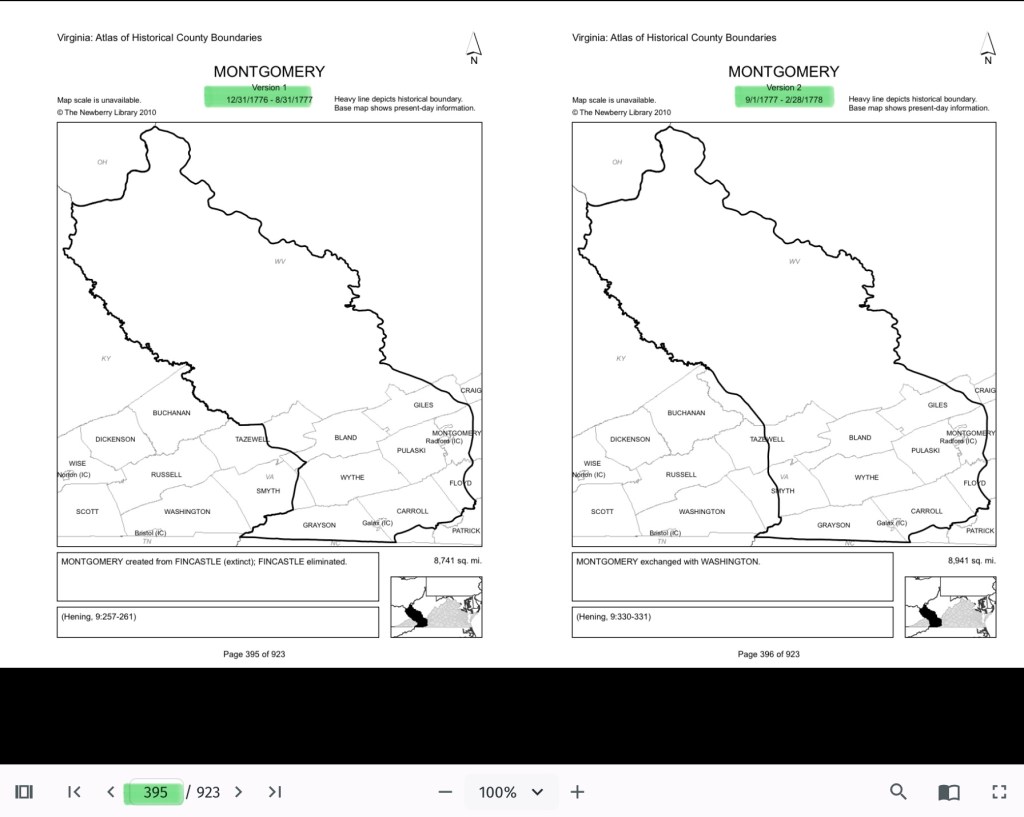

The flip book of maps below is a helpful resource to understand how the boundaries changed with time. Virginia Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. Begin on page 395.

Further Discussion on How Shifting Boundaries Change Lives

Laws & Records

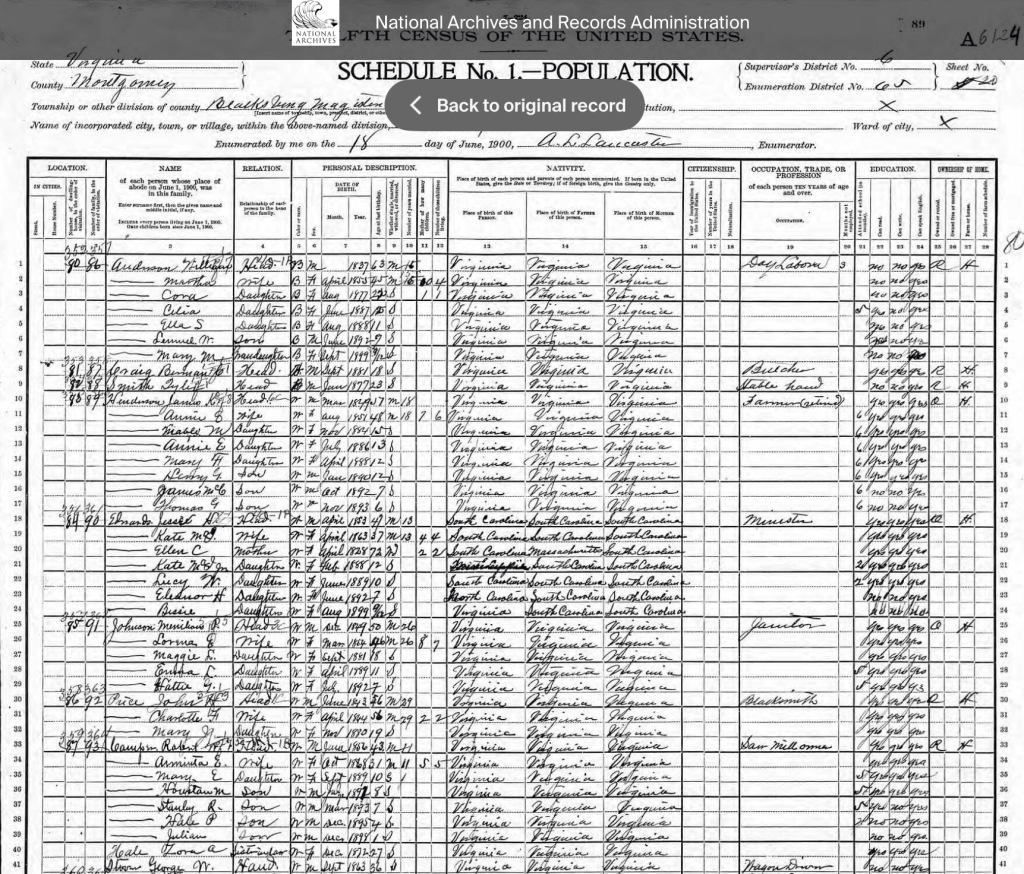

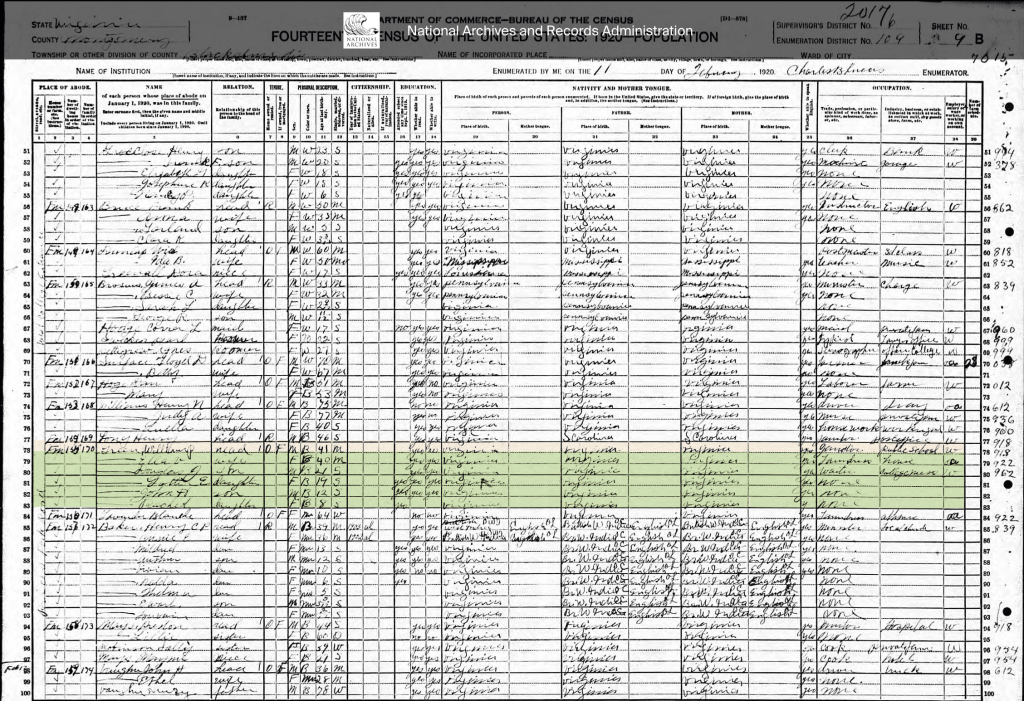

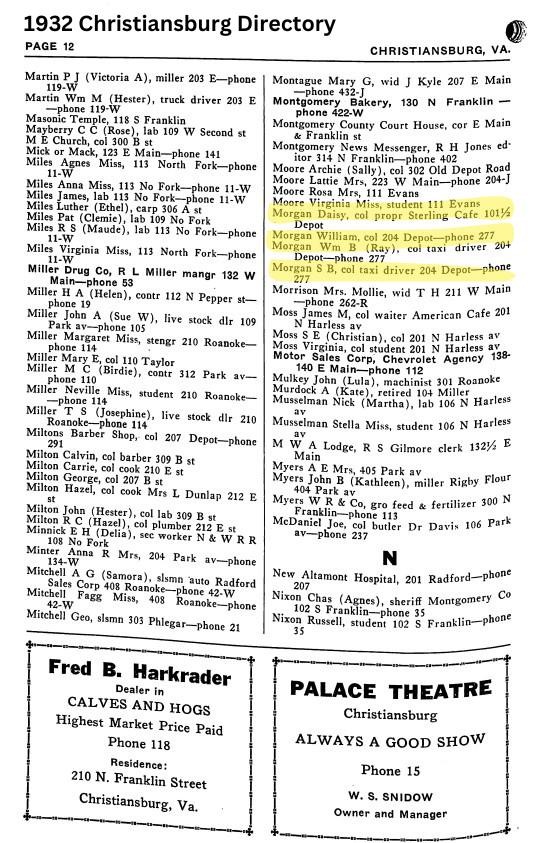

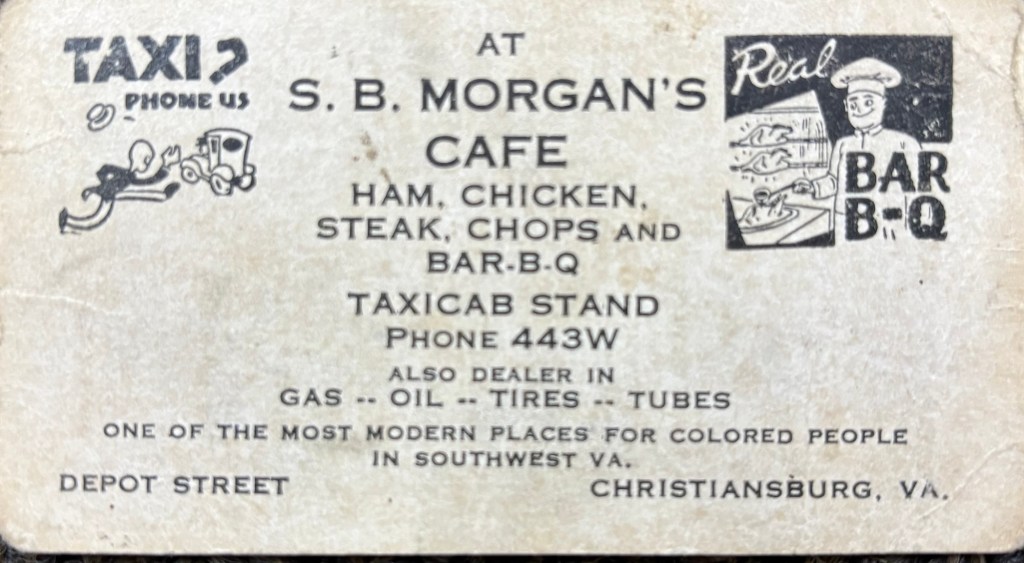

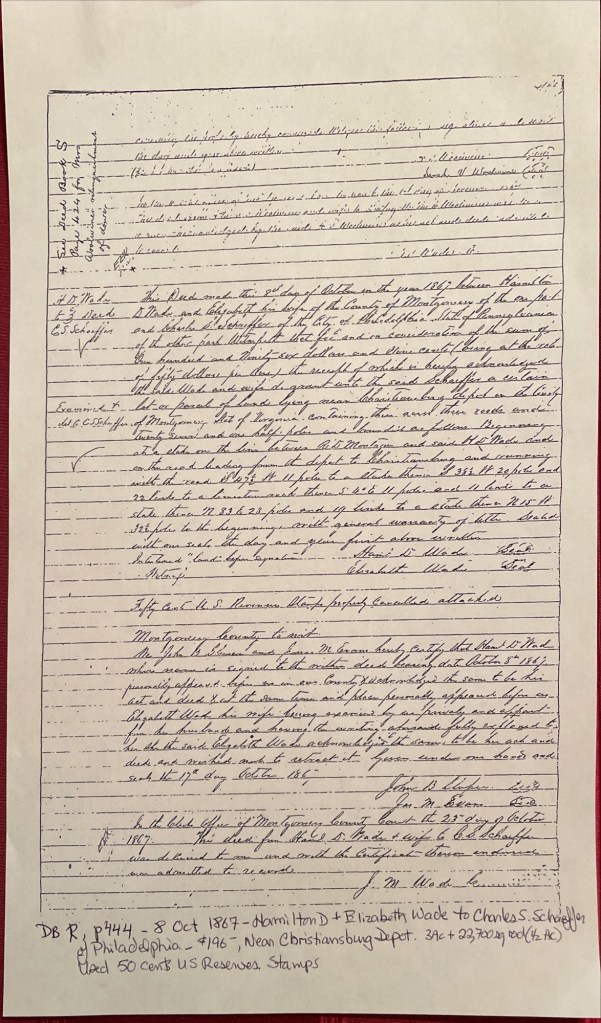

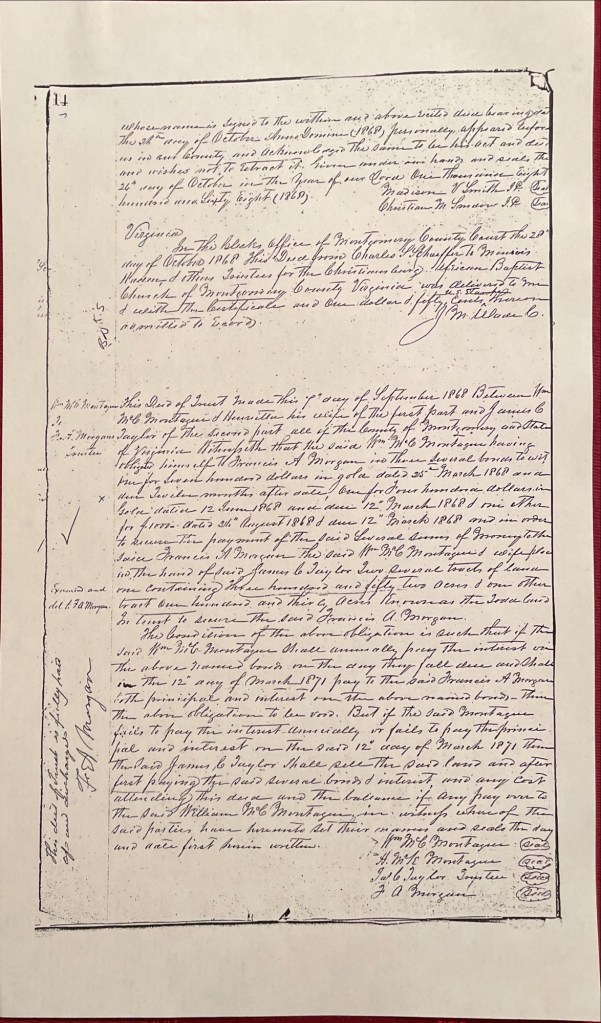

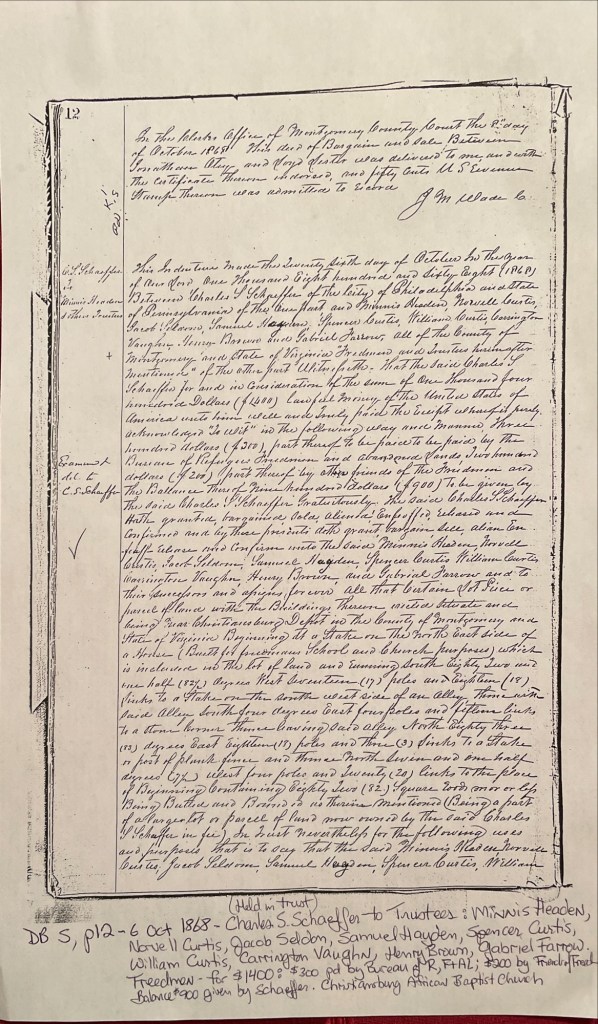

When county boundaries changed, so did the courthouse where records were kept. For enslaved people, this meant that bills of sale, wills, deeds, and manumission papers might end up filed under different counties as the boundaries shifted. After emancipation, the same was true for marriage licenses, labor contracts, and land purchases by freedmen. This scattering of records makes it both complicated when tracing family histories.

Shaping Community, Labor & Education

County lines determined where enslaved people were forced to labor, where patrols were organized, and where courts enforced slavery laws. After emancipation, those same boundaries shaped freedmen’s access to work, land, and schools. For example, as new counties like Giles or Pulaski were created from Montgomery, Freeman might find themselves suddenly in a different jurisdiction, dealing with a new local power structure.

Education also reflected these divisions. Freedmen near Christiansburg had better access to schools supported by the Freedmen’s Bureau, while those in rural reaches of the county received little help.

Courts and Law

During slavery, county seats (like Christiansburg) were centers of trade, law, and the slave market. Enslaved people were taken to county courts for sales, trials, and punishment. After emancipation, those same county seats became the centers where freedmen registered marriages, secured legal recognition, and later sought protection under Reconstruction policies.

Land, Freedom, and Mobility

For freedmen, land ownership was key to independence. But access to land varied widely from one county to another, depending on who owned large estates, which lands were subdivided, and how local officials treated Black landholders. County boundaries thus shaped the possibilities of building self-sustaining communities after emancipation.

More Maps

Virginia Map 1810 found in Brumage-Brummage Family, They are the same family, Monongalia and Marion Counties, West Virginia, Virginia Brumage Wakeman. Montgomery Museum of Art and History, Christiansburg, Virginia