Fisk University has made its Rosenwald School Digital Collection publicly accessible, a significant step in preserving and sharing the history of these important institutions. For Montgomery County, the collection documents the Rosenwald Schools established through the determination and vision of African American communities in Elliston, Pine (Piney) Woods near Riner, Shawsville, and Wake Forest.

Although only the Wake Forest school remains today—adapted for use as a private residence—the collection ensures that the legacy of all three schools endures. These schools stand as a testament to community leadership, resilience, and the transformative power of education during the early twentieth century.

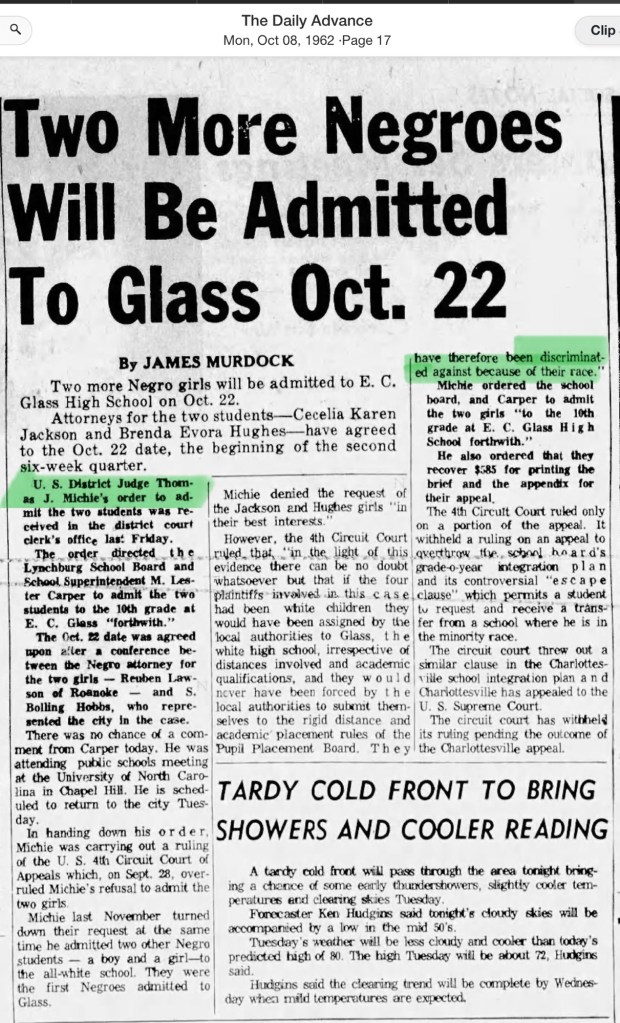

The Story of Rosenwald Schools

The website (scroll down) offers a wealth of information: the story of Julius Rosenwald and his vision, the purpose of the school fund, the significance of the school designs, and the requirement that African American communities contribute a share of the cost. Visitors will also find maps, photographs, and documentation of schools across the region and beyond.

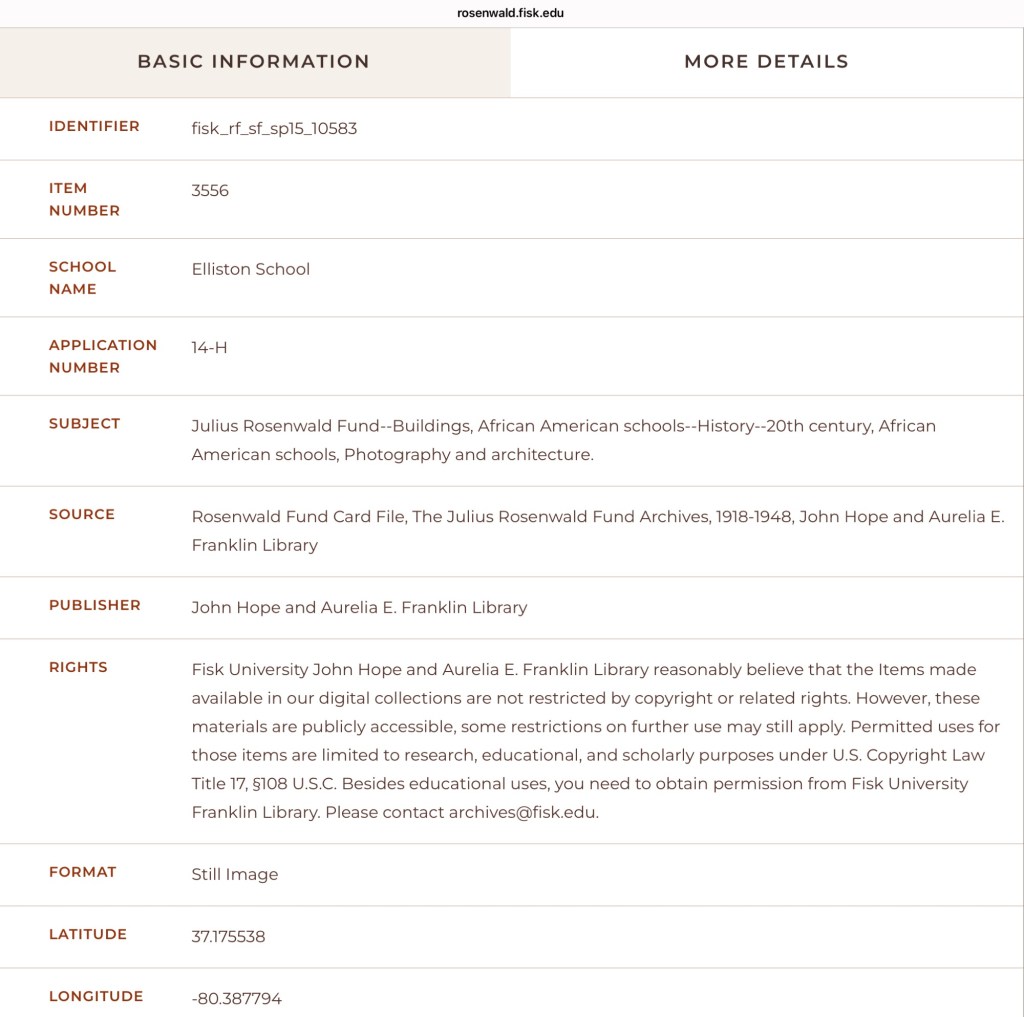

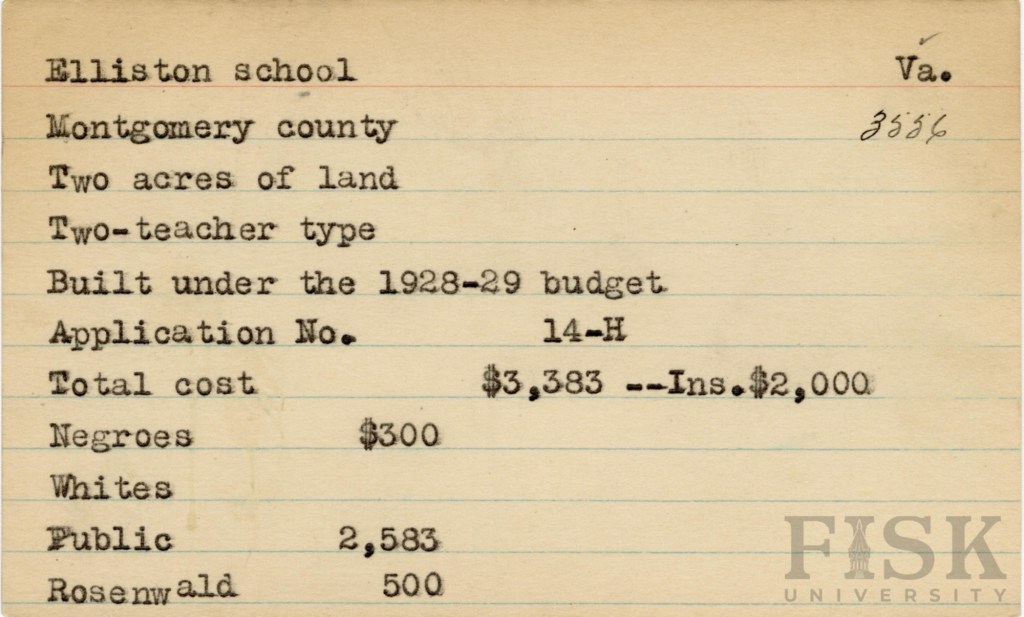

Elliston School

Built in 1928–1929, the Elliston Rosenwald School reflects the determination of the local African American community to provide better educational opportunities for their children. Families in Elliston raised $300 toward the project, which was matched by $500 from the Rosenwald Fund and $2,583 from the Montgomery County School Board.

The school stood on two acres of land and housed two classrooms, each with its own teacher. The school was located on Brake Road, in the Allegheny School District. The legacy: the Elliston Rosenwald School was a center of learning, community, and pride during an era when access to education was hard-won.

Pine Woods School

The Pine Woods Rosenwald School (Piney Woods) was built in a two-teacher design under the supervision of Tuskegee University. The school was sited on Piney Woods Road, in the Auburn School District. While the exact construction date is unknown, records indicate the total cost was $1,075. Of that amount, the Rosenwald Fund contributed $300, the African American community raised $275, and the Montgomery County School Board provided $500.

Unlike white schools of the period, which were fully funded by the School Board, African American families were required to make direct financial contributions toward the construction of their schools. This inequity underscores both the systemic barriers they faced and the extraordinary commitment of the Pine Woods community to ensuring education for their children.

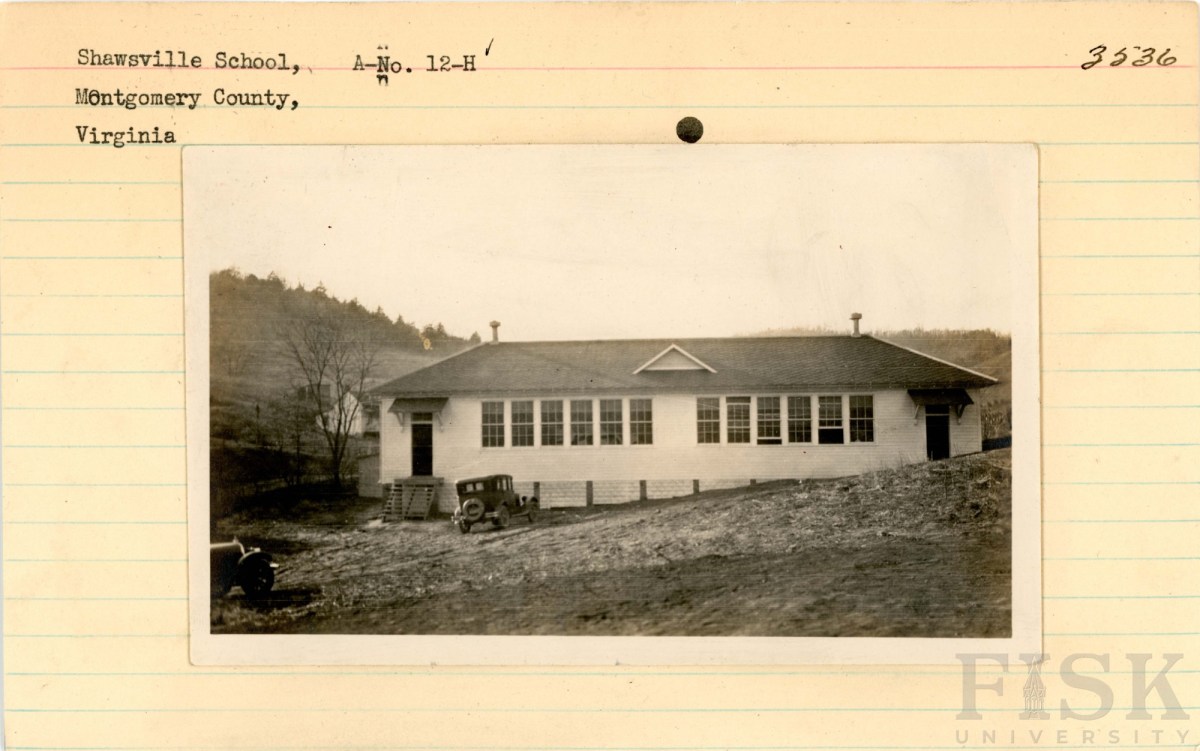

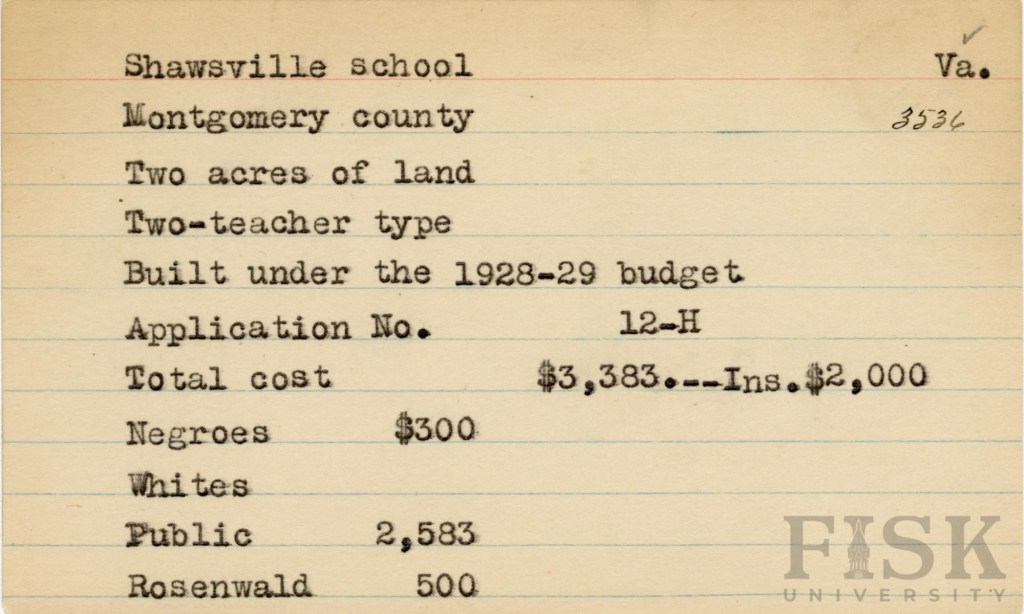

Shawsville School

Constructed between 1928 and 1929, the Shawsville Rosenwald School followed a two-teacher design overseen by the Montgomery County School Board. The total cost of $3,383 was shared among the Rosenwald Fund ($500), the African American community ($300), and the Montgomery County School Board ($2,583).

At the time, Shawsville, of the Allegheny School District, was a thriving hub, energized by railroad service and new road (US Route 11) construction projects. These opportunities drew African American laborers and rail workers to the area, many of whom invested their limited resources into building a school for their children. Their contributions—financial and communal—stand as a testament to the determination of Shawsville’s African American families to secure education despite inequities in public funding.

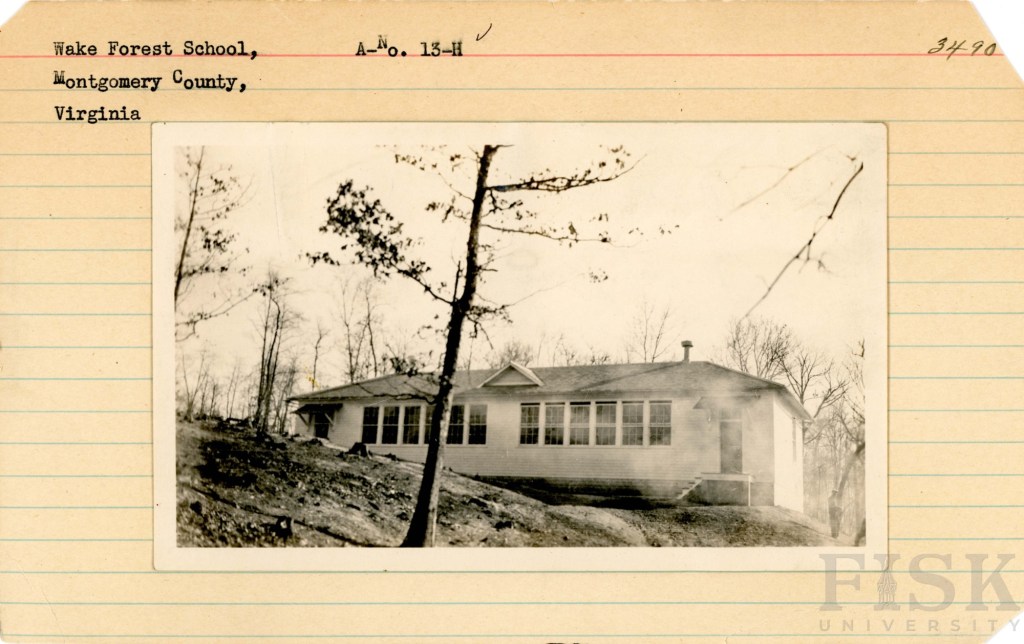

Wake Forest School

Constructed between 1928 and 1929, the Wake Forest Rosenwald School followed a two-teacher design on a two-acre site, in the Blacksburg School District, overseen by the Montgomery County School Board. The project cost $3,383, with funding shared by the Rosenwald Fund ($500), the African American community ($426 in 1928, about $7,500 in today’s value), and the Montgomery County School Board ($2,457). This school is now a private residence.

The Wake Forest community at this time was made up of independent farmers, farm laborers, boatmen, railroad workers, teamsters, and domestic workers. As coal extraction began to rise and reshape the region’s economy, African American families recognized that education would be essential for their children’s future. By pooling their resources—despite economic hardship—they ensured access to schooling that could open paths beyond the limits of labor and provide new opportunities for the next generation.