Montgomery County, Virginia, has never existed in isolation.

The people who have lived here—whether by choice, through enslavement or servitude, or as Indigenous communities who established towns long before European arrival—moved across boundaries freely. They traveled, traded, fought, buried their dead, and carried out the everyday work of survival across what later became county lines.

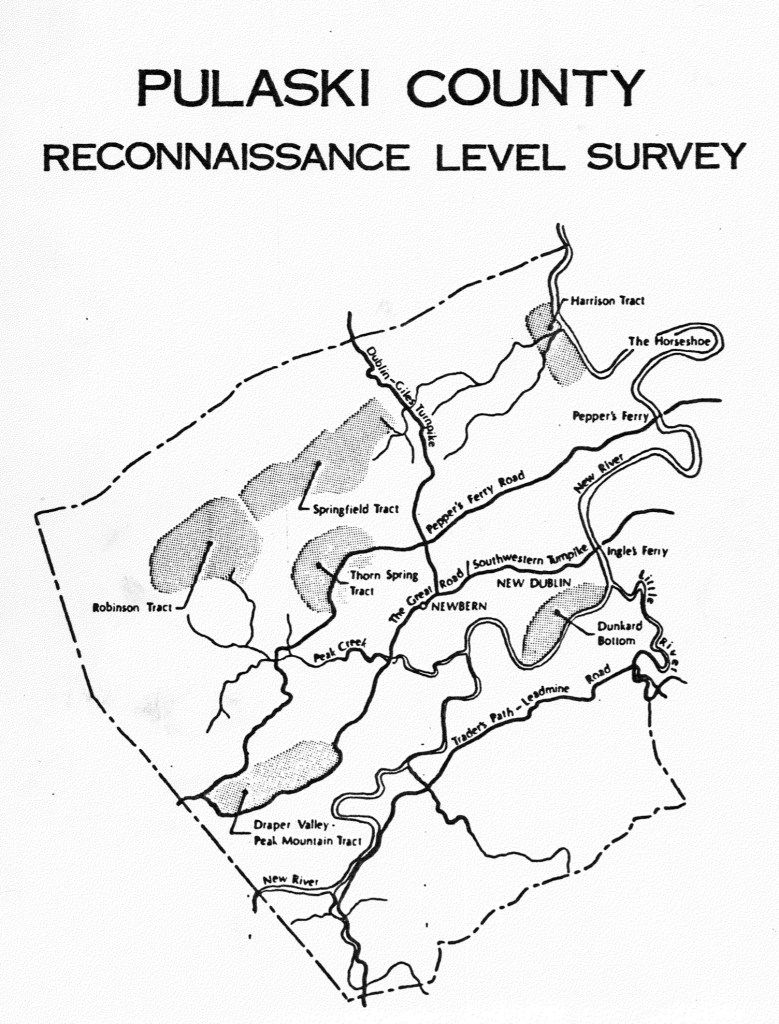

This is why the Pulaski County Reconnaissance Survey, created by Gibson Worsham, Dan Pezzoni, and many others, is such a valuable resource. It provides vital insights into African American history in Southwest Virginia and the greater Central Appalachian region, helping us better understand the interconnected stories that shaped our communities.

This report is fully searchable and contains valuable early documentation on African American schools, churches, and communities. It also includes a generalized map that highlights both early European settlements and land tracts. For example, Dunkard’s Bottom—now submerged beneath Claytor Lake—was once part of an early German settlement.

The report also identifies significant Scotch-Irish tracts such as Draper Valley/Peak Mountain, Harrison, Robinson, Springfield, and Thorn Spring. It notes the communities of Newbern and New Dublin, along with the region’s main transportation routes: Traders Path/Leadmine Road, the Great Road/Wilderness Road/Southwestern Turnpike, Peppers Ferry Road, and the Dublin/Giles Turnpike.

The report offers a clear explanation of the early Importation and Treasury Rights system used to claim land (see pages 23–24). For further detail, see F.B. Kegley, Kegley’s Virginia Frontier, Roanoke, VA: Southwest Virginia Historical Society, 1938. p. 59.

Read the full Pulaski County Reconnaissance Survey report ›

By Gibson Worsham, Dan Pezzoni, Leslie Naranjo-Lupoid, Joseph T Koelbel, Dan Rotenizer, Charlotte Worsham, Vicky Goad, CA Cooper-Ruska

The report contains interesting data about the enslaved, noted on page 44. Also, the churches and New River Village is discussed beginning on page 56.

In Pulaski the pattern of large landholding influenced the ownership of slaves. Whereas in Montgomery County there were 2,219 slaves, and in Pulaski only 1,589 in 1859, eight slaveholders had more than fifty slaves in Pulaski while only two landowners in Montgomery possessed as many. In both counties, however, the majority of owners possessed ten or fewer slaves. During the Civil War, the Confederacy began requisitioning slaves to work in the war effort. At the beginning of the war many slaves were requisitioned and shipped to Richmond to fortify the state capital. In the following three years slaves were requisitioned four times so that by 1865 the county found it could no longer comply as it was being drained of free and slave manpower, food supplies and money.

Pulaski Timeline

Timeline was created for the 2030 Comprehensive Plan of Pulaski County

A Note on the Language in the County’s Comprehensive Plan

As part of Montgomery County’s 30-year Comprehensive Plan, a historical timeline was created. While the dates provided are generally accurate, the language used to describe Indigenous people and borderlands does not align with our values.

We want our readers to be aware that these depictions reflect the language of the plan’s authors—not the values or beliefs of this website. Our commitment is to present history in a way that acknowledges the dignity, presence, and contributions of all people who have lived in this region.

Note that the African American community of “New River” came to exist after emancipation.