On July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass delivered his powerful speech, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” to the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York. In it, he confronted the meaning of Independence Day from the perspective of those still enslaved, asking what freedom could mean in a nation that denied it to millions.

The copies of both the full version and excerpts are available.

Excerpt Versions

- Excerpt version, pdf

- Excerpt version, National Constitution Center

- Excerpt version , Underground Railroad

Full Versions

Audio Versions

Context and Biographical Information

Back Story Radio – excellent production and provides insightful context to the time and place.

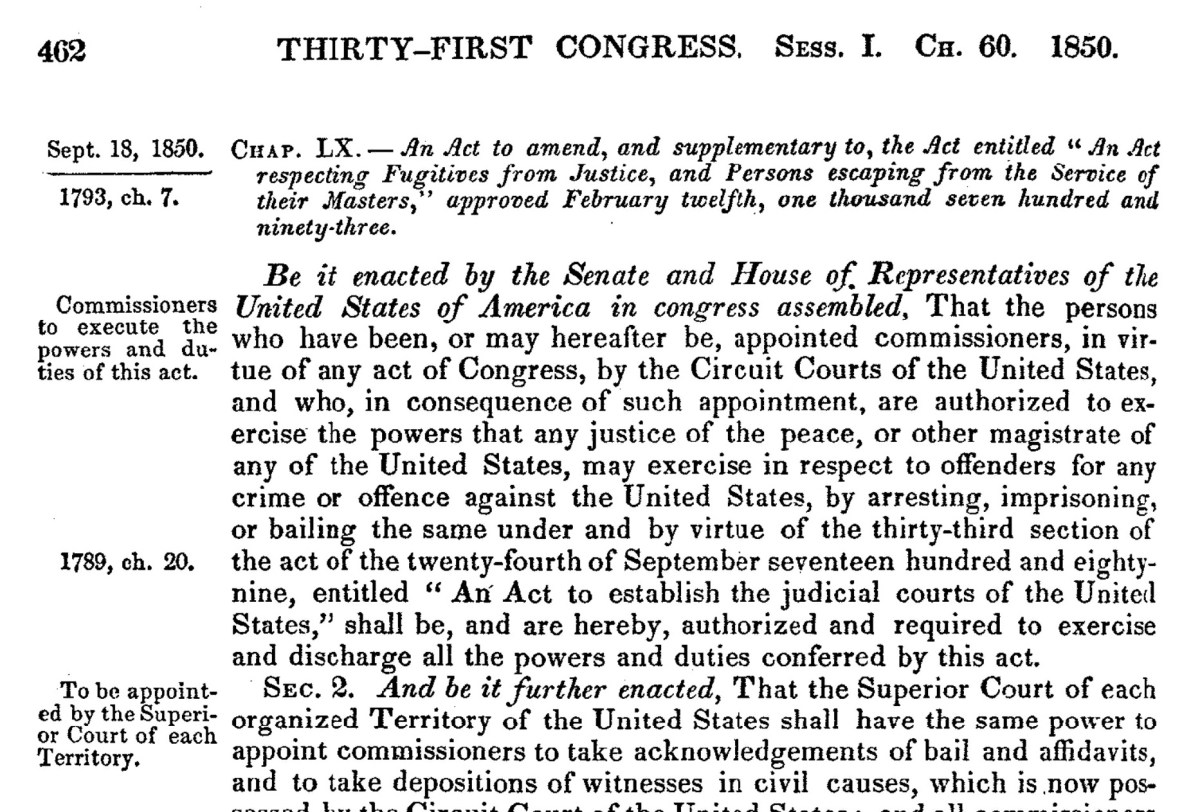

The Compromise of 1850 included the Fugitive Slave Act, a federal law signed just two years before Mr. Douglass’s 1852 speech. As historian Eric Foner has noted, this act demonstrates that pro-slavery states were willing to abandon their usual defense of states’ rights when it came to protecting the institution of chattel slavery. Eric Foner on the Fugitive Slave Act.

EdSiteMent , National Endowment for the Humanities, provides information, context and lesson plans.

Library of Congress, papers and documents of Frederick Douglass

Original Biographies that are available online

Timeline of Mr Douglass’ life, presented by the Library of Congress. Brief Summary Based on the Library of Congress

Frederick Douglass married Anna Murray in 1838. Together, they had five children: Rosetta (1839), Lewis Henry (1840), Frederick Jr. (dates vary, likely born around 1842–1843), Charles Remond (1844), and Annie (1849). The family moved to Rochester, New York in 1847, where Douglass continued his abolitionist work.

In 1859, following the failed John Brown raid, Douglass fled briefly to Canada to avoid arrest, returning in 1860—the same year his daughter Annie died. That year, Abraham Lincoln was elected president, and South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union.

During the Civil War, slavery was abolished in Washington, D.C. in 1862, and the Emancipation Proclamation took effect in 1863, freeing enslaved people in Confederate states. That year, Douglass met with President Lincoln to advocate for Black soldiers and equal treatment.

On April 9, 1865, General Lee surrendered to Grant, effectively ending the Civil War. Lincoln was assassinated five days later. The 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery, was ratified later that year.

Douglass remained active during Reconstruction, fighting for civil rights and women’s suffrage. In 1870, the 15th Amendment guaranteed the right to vote regardless of race. That same year, after a suspicious fire at their Rochester home, the Douglass family moved to Washington, D.C., where Douglass was nominated for vice president by the Equal Rights Party, alongside presidential candidate Victoria Woodhull.

In 1874, Douglass became president of the Freedmen’s Savings Bank in a final effort to save the institution, which was failing and held the savings of many newly freed people. In 1875, Congress passed a Civil Rights Act to combat public discrimination, but in 1883 the U.S. Supreme Court rules the act was unconstitutional.

By 1877, Douglass had been appointed U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia and later purchased a home in Anacostia (now Cedar Hill). Anna Murray Douglass, his wife of 43 years, died in 1881. He married Helen Pitts in 1884.

From 1889 to 1891, Douglass served as U.S. minister to Haiti and chargé d’affaires to Santo Domingo. He died unexpectedly in 1895.

Quotes From “What To A Slave Is the Fourth of July?”

Now, take the Constitution according to its plain reading, and I defy the presentation of a single proslavery clause in it. On the other hand it will be found to contain principles and purposes, entirely hostile to the existence of slavery. . . .

Great streams are not easily turned from channels, worn deep in the course of ages. They may sometimes rise in quiet and stately majesty, and inundate the land, refreshing and fertilizing the earth with their mysterious properties. They may also rise in wrath and fury, and bear away, on their angry waves, the accumulated wealth of years of toil and hardship. They, however, gradually flow back to the same old channel, and flow on as serenely as ever. But, while the river may not be turned aside, it may dry up, and leave nothing behind but the withered branch, and the unsightly rock, to howl in the abyss—sweeping wind, the sad tale of departed glory. As with rivers so with nations.